Source: shondaland.

Inspired by social media and pop culture figures like Beyoncé and Jay-Z, a new crop of art lovers is building collections of their own.

Growing up, Seble Asfaw was always exposed to art that was inextricably linked to her ancestry and cultural heritage.

“I was surrounded by Ethiopian artifacts since childhood that all had significant meaning to me and my family,” Asfaw tells Shondaland. “This initial exposure made me want to start educating myself on classical African art. I enjoy learning about the intention behind why a piece is created and how a group of people would use it.”

Asfaw is a program manager in New York City, and her self-education led her to an even deeper appreciation for the diversity of African art. She felt especially drawn to classical African art pieces — including masks, figures, and sculptures.

“For me, it’s a form of connecting to a part of myself and my lineage,” Asfaw says. “Right now, I’m seeing a lot of attention on figurative, contemporary, or abstract Black or African art. This is a beautiful thing, of course, but I do believe we need to make room for classical African art in these conversations, as it very much impacts what artists are creating now — it connects the dots and bridges the gap between the past and present.”

Asfaw established her own art consulting company, Misgana African Art, to help connect collectors, curators, and institutions to works from across Africa and the African diaspora.

“The art world has a long way to go when it comes to diverse cultural representation,” Asfaw says. “I have met some incredible people in the space that have guided, supported, and empowered me. However, there have also been many times where I’ve felt like the world of classical African art is not for me or out of reach, mostly because the space is so heavily dominated by white collectors, dealers, and gallerists.”

There are also very few women gallerists in this area overall, which is why she wanted to launch her own business in this space. “[It’s] why I encourage other women to take this journey with me,” Asfaw says. “I’ve still pressed on because I keep being guided back to the importance of learning about classical African art and having more people like me reclaim ownership of artwork that connects so deeply with our history.”

One of the first pieces Asfaw collected was a 19th-century Shona snuff container from Zimbabwe. A mixture of indigenous leaves, snuff is ground to a powder and inhaled. “It was taken at all important ceremonies and was believed to facilitate communication with ancestors,” she says.

Another piece in her budding collection is a 19th-century South African beaded necklace. She’s particularly fond of South African beadwork because of the vibrant patterns and colors.

“It is its own visual language,” Asfaw says. “Beadwork in the 19th century was done only by women, who also made beautiful earthenware pots. Men made the wood objects, such as headrests, platters, and other utilitarian objects.”

Asfaw acquired both pieces from Jacaranda gallery in New York City. “Established in 2007, Jacaranda sells museum-quality art to collectors and museums worldwide. Initially specializing in the traditional arts of South and East Africa, Jacaranda now deals in art from all regions of Africa, as well as Oceania and North America,” according to the Jacaranda site.

Dori Rootenberg, a co-director of the gallery, studied art history and began frequenting museums in college. “I was always drawn to the African galleries,” she says. “When I got married, eventually my husband and I started collecting African art.”

After a number of years of collecting, they decided to turn it into a business, and their gallery was born. Since then, she’s worked with all sorts of collectors but points out that the pandemic dramatically shifted the landscape of who, exactly, collects art.

With everybody stuck at home and unable to visit galleries, museums, and art fairs, the IRL nature of art browsing and collecting quickly moved to the internet.

“Many people spent a huge amount of time online,” Rootenberg says. “And art lovers in general probably spent a huge amount of time online just getting their daily fix of what was happening in the art world.”

The beauty of social media, Rootenberg explains, is that dealers and galleries can still post what they’re offering. And since cell phone photography has vastly improved in the last few years, seeing an artwork in person isn’t as important as it once was.

“It really leveled the playing field,” she says. “Some people may feel a bit intimidated. People who didn’t necessarily have a comfort level going into a fancy gallery said, ‘I can just look online and sit in my pajamas. I don’t have to get dressed up and go to an opening.’”

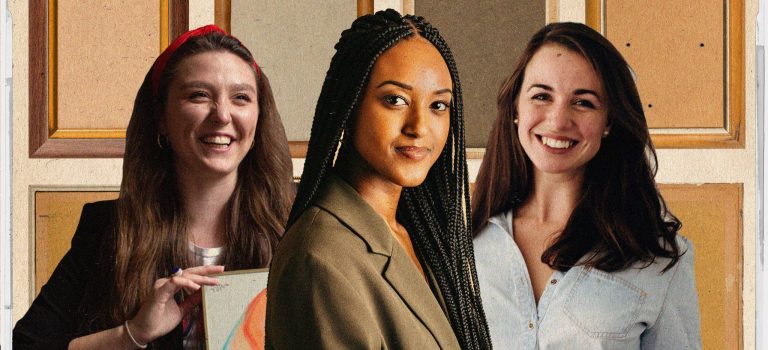

Alix Greenberg, the founder and CEO of ArtSugar, a charity-driven retailer offering an exclusive assortment of curated art and home goods, worked in the fine-art world for years.

“Instagram wasn’t really influencing what people bought [back then],” Greenberg says. “They didn’t really know the artists and weren’t really connected to them. They were hearing about them through museums or their representation.”

It’s different now, with anyone having the ability to collect directly from artists, which has totally changed the landscape and pricing transparency. “The art world should be more open,” Greenberg says, “which is why I started my company ArtSugar so we could democratize art, which should be accessible to everyone.”

Pop culture is another element influencing the demographics of the “typical” art collector. Music magnates like Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Madonna, Diddy, Sir Elton John, and Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys are just some of the celebrities known for their impressive art collections. And with social media demystifying the art of, well, art collecting, it’s no wonder collectors are getting younger and younger.

“I’ve really, really noticed a massive uplift in younger people collecting art, even compared to when I first started collecting a few years ago,” says Charlotte Fletcher, a cofounder of Christie’s the Young Collectors Club. “More young people have had that door open to them.”

What’s more, most of the younger art collectors Fletcher knows are women. “When you think about how many men make up the general body of art collectors, that’s really exciting,” she says. “It will have quite an impact on the whole market in the future.”

Alexandra Steinacker Clark, an American-Austrian art historian, curator, and writer based in London, specializes in contemporary art, specifically feminism and artificial intelligence in artistic practice. She currently works at Sotheby’s auction house, is an ambassador for MTArt Agency, and is the founder and host of the podcast All About Art.

“Supporting living artists is what got me started in collecting,” Clark says. “Now I love collecting art from artists I work with and greatly admire. It means a lot to have pieces in my collection to look at and admire daily that I also associate with fond experiences and memories.”

She recalls wanting to collect a piece by an Austrian artist after falling in love with her work. The piece she had her eye on ended up being submitted for an art prize. Clark recently learned that the artist has won the prize.

“So, two years after the first studio visit, I remain at square one of finding a specific work of hers that I want in my collection,” Clark says. “My favorites keep getting snapped up before I can get my hands on them.”

For anyone looking to start, or maybe expand, an art collection, Clark’s best advice is getting to know your tastes before buying anything big — both in terms of size and price.

“Read some articles, listen to arty podcasts, and learn a bit more about what you like, because it will change over time,” Clark says. “When you collect art, you live with it, so keep that in mind.”