Source: Artsy

The causal links between price points on the secondary auction market and supply, demand, critical reputation, celebrity, cultural tastes, and the wider economy are complex. However, death, both timely and untimely, has the potential to radically shift all these relationships and produce a change in price.

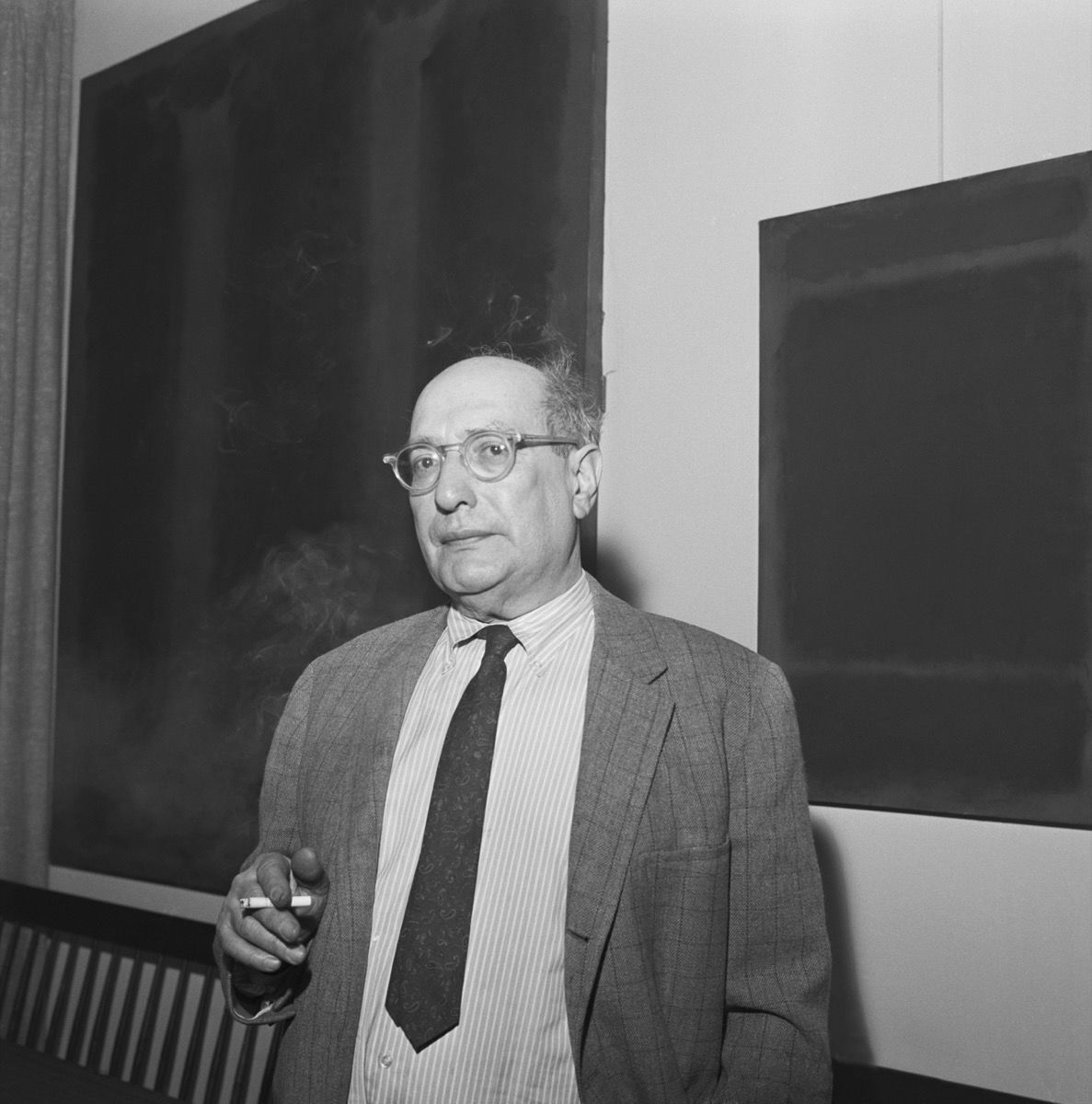

During the 1970s, a long-running legal case concerning Mark Rothko’s estate dominated news in the art world. After Rothko’s death by suicide in 1970, a fierce battle waged between his heirs, executors, and dealers at Marlborough Gallery. The abstract artist’s death at age 66 shocked the art world and created a sudden production gap in any future market for his work. The average U.S. life expectancy in 1970 had been around 70.81 years. Rothko, a wealthy, educated, urban man, might have been demographically expected to live a lot longer.

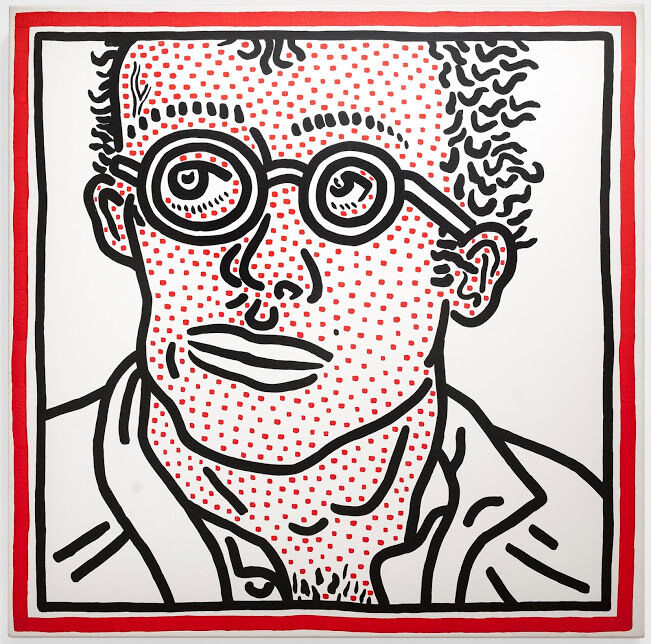

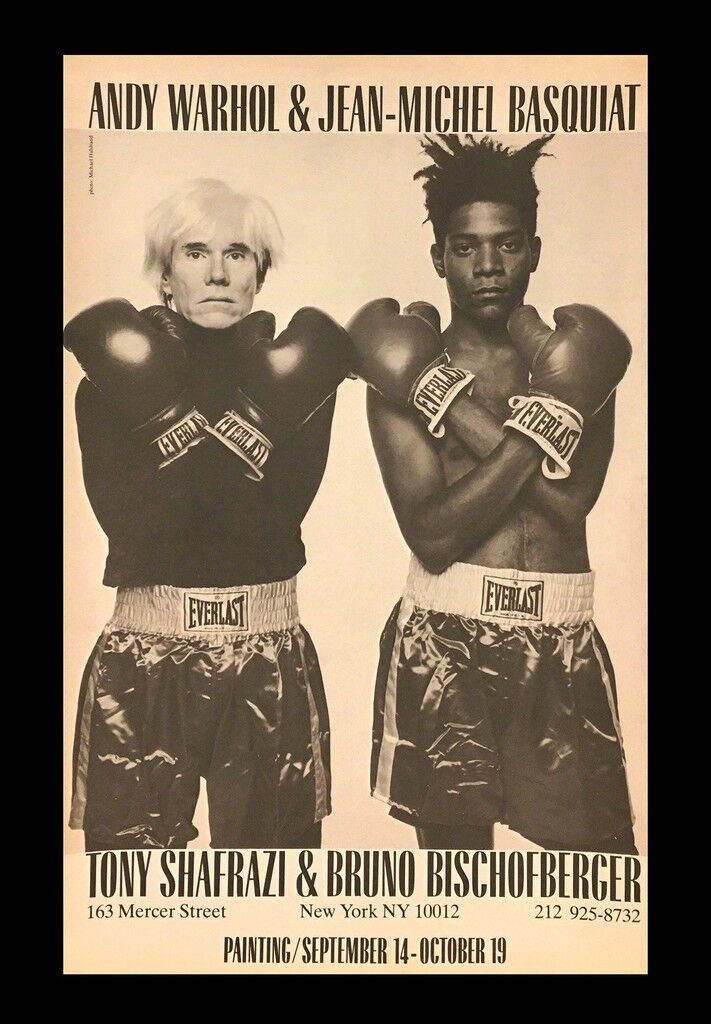

When he died, Rothko left a stellar critical reputation, a suddenly restricted supply of 798 artworks of tremendous value, and two children with claims on his estate. Unlike later artists who have died in an untimely fashion—such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, or more recently Noah Davis and Matthew Wong — Rothko’s death had all the necessary factors to set off a protracted dispute that would become a symbol of the darker side of the art market. Rothko’s executors were called “wrongful and indeed shocking” by the New York Court of Appeals after attempting to withhold work from the estate to their own benefit. They also attempted to restrict what Marlborough put on the market, stipulating that the gallery “could sell up to 35 paintings a year from each of two groups, pre-1947 and post-1947, for 12 years at the best price obtainable but not less than the appraised estate value.”

Anticipating the “death effect”

Portrait of Mark Rothko. Photo by Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images.

Whether they buy works by Rothko, Wong, or Andy Warhol, most collectors who bet on the price trajectories of artworks will be concerned about oversupply. This threat of oversupply flooding the market and dropping prices comes from the sole producer of goods in circulation—the artist—who is a “durable goods monopolist,” a term used by Nobel Prize–winning economist Ronald Coase. This academic label, explained by journalist Anna Louie Sussman in an Artsy article examining the so-called “death effect,” means “a supplier with a monopoly on a durable good (say, a painting intended to last over time) [who] can take certain actions to assure buyers that she or he will not ‘spoil’ the market by flooding it with a surplus of goods. This serves to maintain a stable price.”

The causal links between price points on the secondary auction market and supply, demand, critical reputation, celebrity, cultural tastes, and the wider economy are complex. However, death, both timely and untimely, has the potential to radically shift all these relationships and produce a change in price.

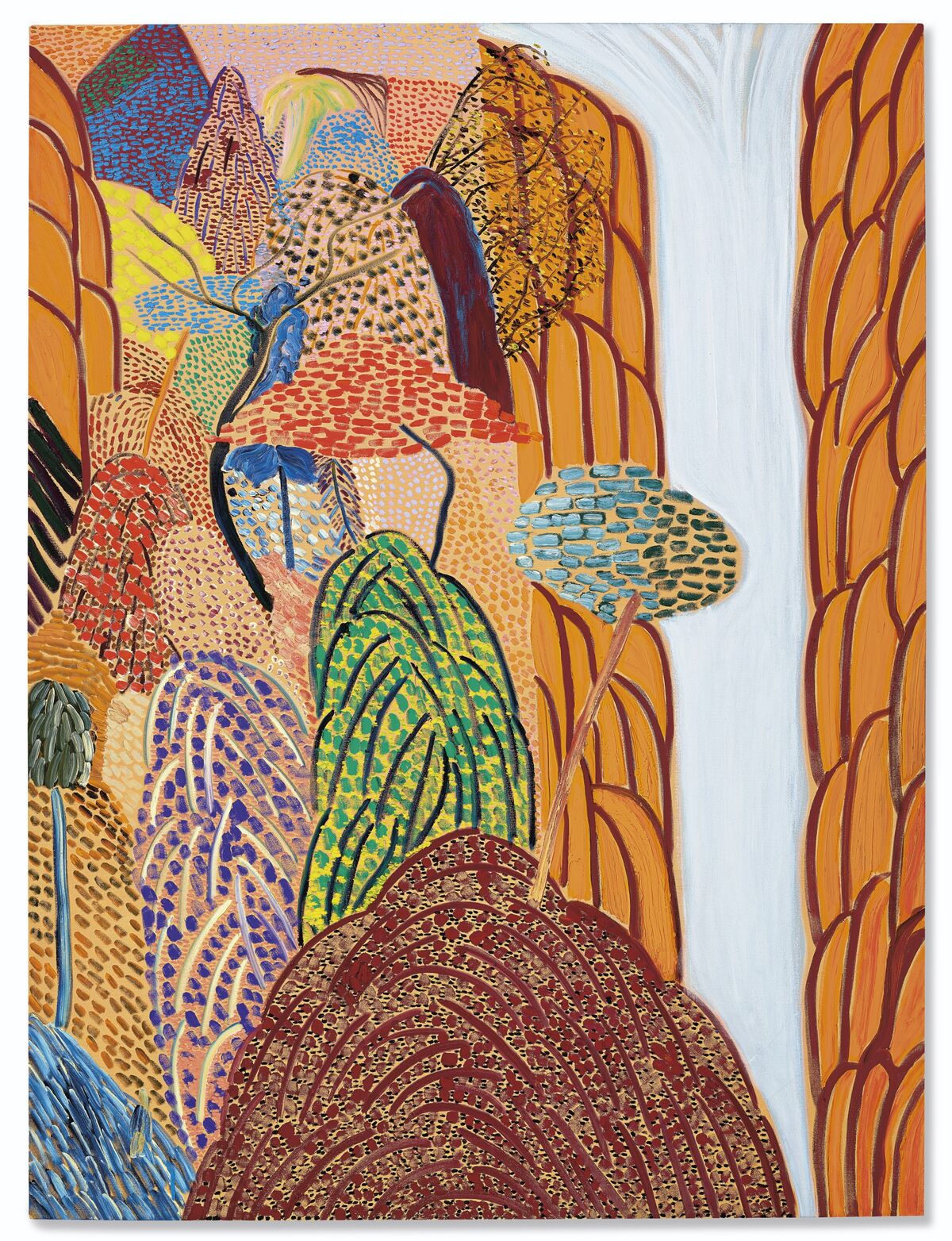

Matthew Wong, Shangri-La, 2017. Courtesy of Christie’s.

Although many individual collectors are motivated by aesthetic pleasure, a portion of buyers see artworks primarily as speculative commodities. “[There is a] rise of a type of dealer-collector, who buys for speculative investment, often outside the usual run of galleries—through auction or from other collectors,” Julian Stallabrass, a professor of modern and contemporary art at the Courtauld Institute of Art, wrote in his book Art Incorporated: The Story of Contemporary Art (2004). “The result of such activity…is that galleries have less control over artists’ prices, and have to respond to their artist’s positions in the secondary market.”

When an artist dies expectedly, at or above the average life expectancy, there is a resultant “death effect” in the secondary market. According to The Economics of American Art by Robert B. Ekelund Jr., John D. Jackson, and Robert D. Tollison, this death effect causes prices, on average, to go up steadily for five years prior to death and then drop immediately after. The price rises because many speculators look forward to a restriction in supply at a point of high consumer regard. The price then drops in response to fear about dealers, galleries, and heirs flooding the market with valuable work.

Flipping and auction flops

On the opposite side of the age spectrum, market speculators “flip” artworks by hyping up young emerging artists and spectacularly raising their auction prices over a short time. For instance, according to Bloomberg, the artist Oscar Murillo’s average prices on the primary market in 2011 were between $2,500 and $8,500. In 2013 alone, $4.8 million had been spent on Murillo’s work at auction. This will have benefited speculators who spotted the Colombian artist’s rise early. By inflating the price of an emerging artist’s works, a buyer can supplement their base level of reputation and value, and, to an extent, bolster the artist’s standing, though doing so also creates a certain amount of risk.

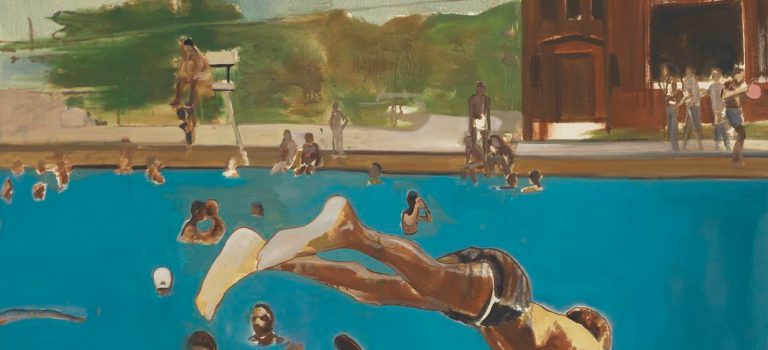

But what happens when an artist dies in an untimely fashion? What factors, such as fame, marketability, and mass and critical appeal, ensure their work a spot in the top rungs of auction sales? Four artists—Basquiat, Haring, Davis, and Wong—provide interesting case studies.

Basquiat and Haring died in 1988 and 1990, respectively, victims of twin epidemics: opiates and AIDS. Both artists were stars of the East Village art scene in New York City and had secured, by age 27 and 31, respectively, a significant level of fame. Basquiat exhibited, for instance, at Documenta, Gagosian, and in the Whitney Biennial, while Haring made appearances at Documenta, the São Paulo Biennial, and the Stedelijk Museum.

Over the following three decades, their work has reached astronomical highs at auction. In 2017, Basquiat’s skull painting Untitled (1982) sold for $110.4 million at Sotheby’s, making him the most expensive American artist at auction. In the same year, the auction house sold Haring’s Untitled (1982), a painting on a vinyl tarp, for $6.5 million, which remains the artist’s auction record.

Despite Basquiat’s early fame, during his lifetime his auction estimates could still be low. Six months before his death in 1988, Sotheby’s sold Texas (1983) for $7,150 (above its high estimate of $6,000), although another oil painting at the same sale went for substantially more, at $23,100 (within its estimate of $20,000 to $25,000). Six months before Haring’s death, his work was selling for considerably higher prices already on the secondary market, and occasionally soaring above auction estimates: For instance, Untitled (1984) sold for $126,500 over a high estimate of $30,000 at a Sotheby’s sale in October 1989.

There is little resemblance between Basquiat’s and Haring’s auction trajectories before their deaths. However, both artists’ sales rise above estimates shortly after their deaths, dip, and then gradually grow again before slamming into a brick wall between 1990 and 1991, when many of their works failed to sell at auction, fell short of their estimates, or were withdrawn. Multiple factors might have led to this dropoff, including the global recession of the early 1990s (when, in 1991, the U.S. economy’s GDP shrank by 0.1% and unemployment reached 6.9%), changes in cultural taste, and tactically reduced demand from speculators anticipating the death effect.

“[An] issue to consider is that because the ‘death effect’ is so well known within the art market, it paradoxically does not always materialize,” said Olav Velthuis, author of Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art (2005). “Many collectors may decide to sell work by the artist after she dies, they expect prices to rise, the market gets flooded, and paradoxically prices are depressed rather than inflated.”

Exceptions, not the rule

The painters Noah Davis and Matthew Wong, who died in 2015 and 2019 at ages 32 and 35, respectively, have both made headlines recently due to surges in prices for their works at auction. In March and June of this year, Davis’s paintings In Search of Gallerius Maximumianus (2009) and Untitled (Kids in the Front Yard) (2010) both sold for $400,000, at Phillips and Sotheby’s, respectively. And earlier this month, Wong’s painting Shangri-La (2017) skyrocketed from an estimate of $500,000 to $700,000 (a big jump in itself from previous estimates) to a final price of $4.4 million at a Christie’s day sale.

Velthuis thinks “the spike in prices after the tragic deaths of Matthew Wong or Noah Davis is the exception, not the rule,” he said, adding that “the question is how long it will last.” Instead, Velthuis assigned a higher probability of prices decreasing for most artists who die or stop producing before average expectancy: “In fact, the younger an artist is when she dies, the less likely the death effect will materialize; for some the price effect has even been negative.” He added: “One explanation is that because of the young age, they have had relatively little time to build up a stable reputation. This uncertainty may be one reason why collectors may be cautious in paying higher prices.”

Helen Molesworth, who curated a posthumous Davis exhibition at David Zwirner at the beginning of the year, thinks prices are ultimately downstream from aesthetics. “I’m not surprised by the jump in prices for Davis’s work. Since his passing, awareness of [him], both as a painter and as the inventor of the Underground Museum, has grown steadily,” she said. “For the vast majority of people who have been riveted by his paintings, the dollar amount attached to them is not the most interesting way to engage with [an] incredible body of work.”

Molesworth added that prices produced “in a marketplace as careless towards its subjects as the auction” should not be the final measure of the value of works by important artists such as Davis.

Samuel McIlhagga