Source: Artsy

Curator Glenn Adamson explores the history of the crafts movement for art-world recognition and explains why craftspeople should not be put back on the sidelines.

“I’d give anything in the world if that little girl with the red hair would come over and sit with me.” That’s Charlie Brown, in the first mention of his schoolyard crush, published in 1961. That is about the same time the studio craft movement conceived its longing for art-world recognition. Inspired by the revolutionary works of ceramist.

All good metaphors must come to an end, though. Charlie Brown got his first kiss in a 1977 television special. It took craft quite a bit longer, but look around today, and you would hardly know that a hierarchy had ever existed. Things changed first for ceramics, with a bellwether exhibition titled “Makers and Modelers: Works in Ceramic” at Gladstone Gallery, in 2007. Hot on its heels was “Dirt on Delight: Impulses That Form Clay,” curated by Ingrid Schaffner and Jenelle Porter at the ICA Philadelphia. And then, suddenly, ceramics seemed to be everywhere: at the fairs, in the galleries, and on auction blocks. Voulkos underwent a dramatic reappraisal—in 2017, his monumental sculpture Rondena (1958) smashed his auction record when it sold for $915,000, or nearly double its high estimate, at a Phillips evening sale—as did others in his circle, like Ken Price and John Mason (the latter is the subject of a new solo show at Gagosian).

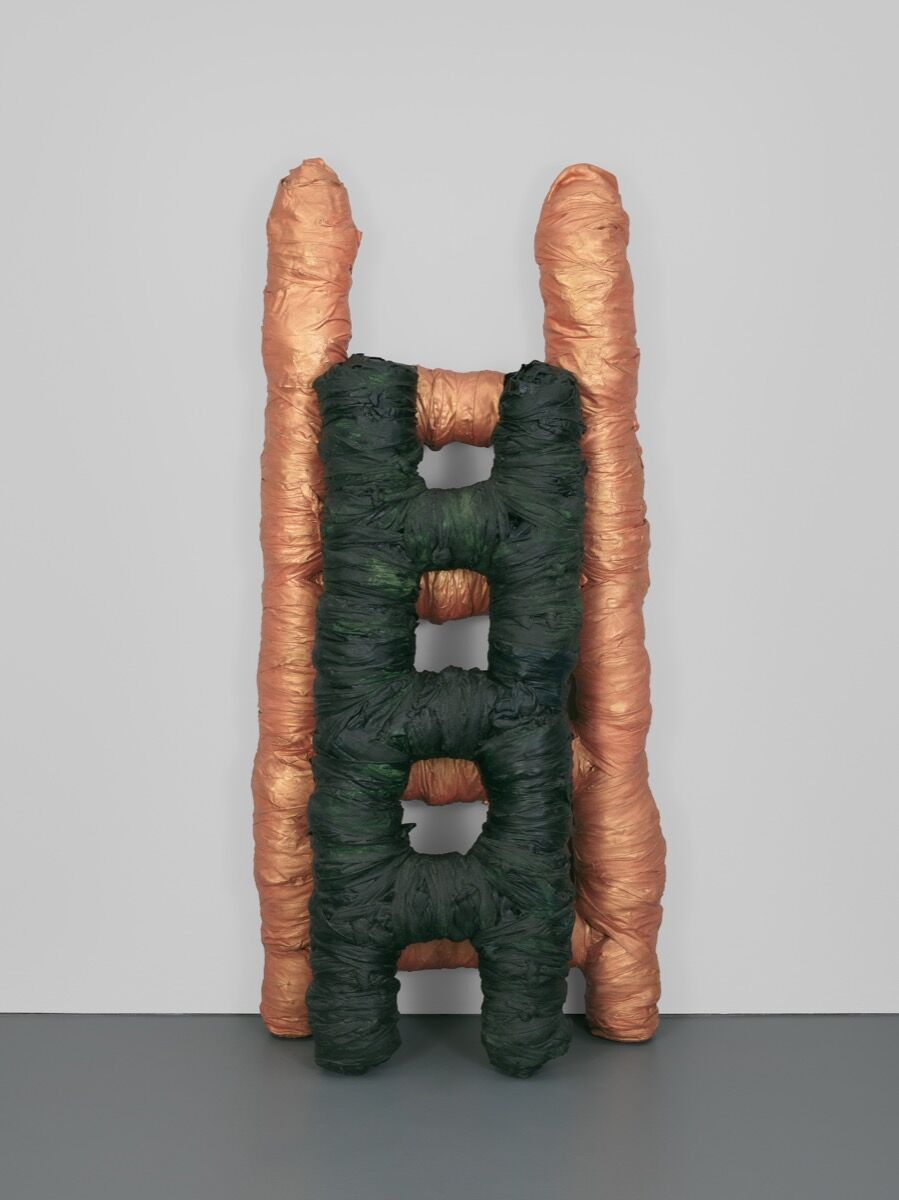

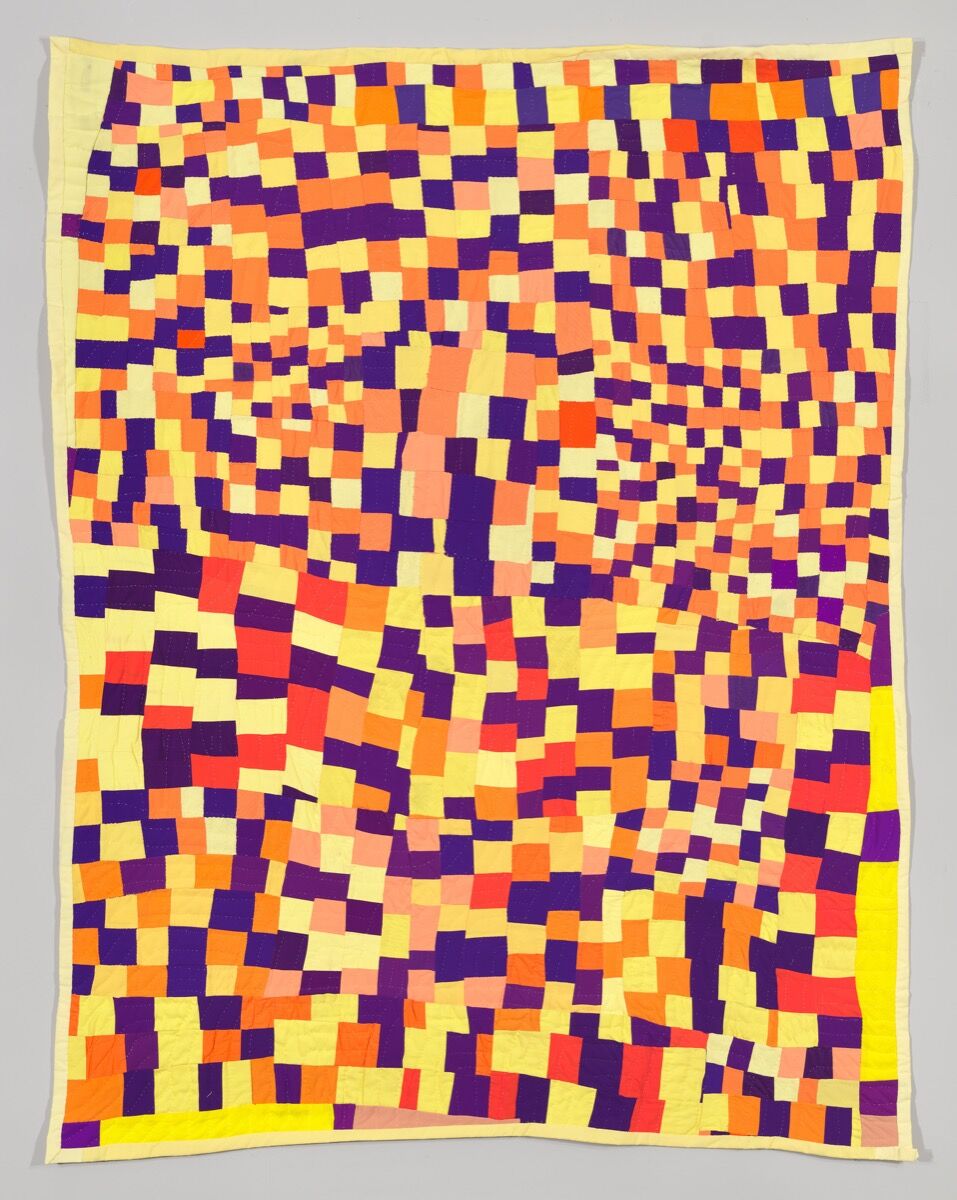

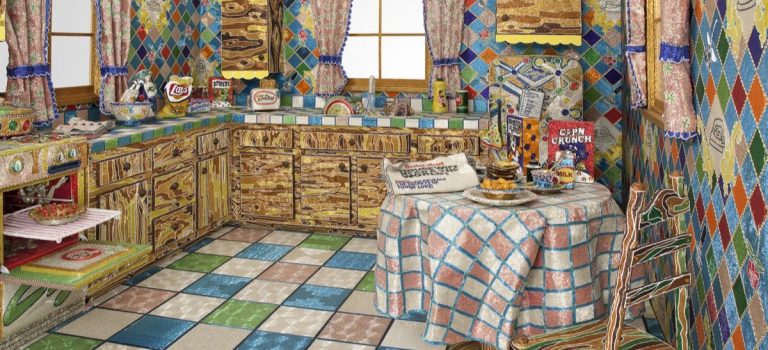

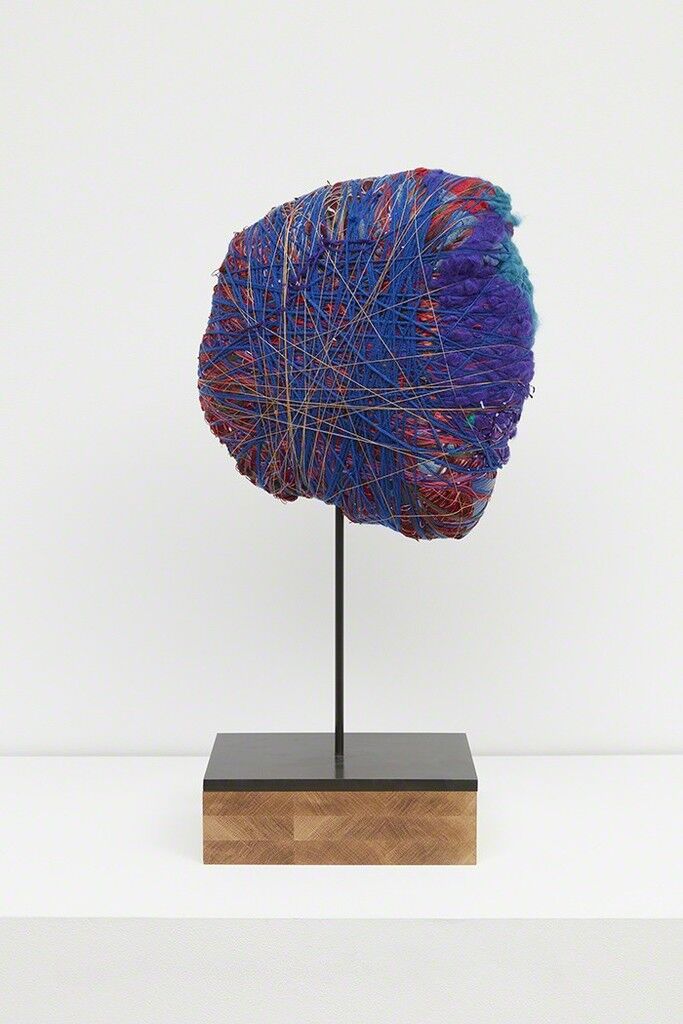

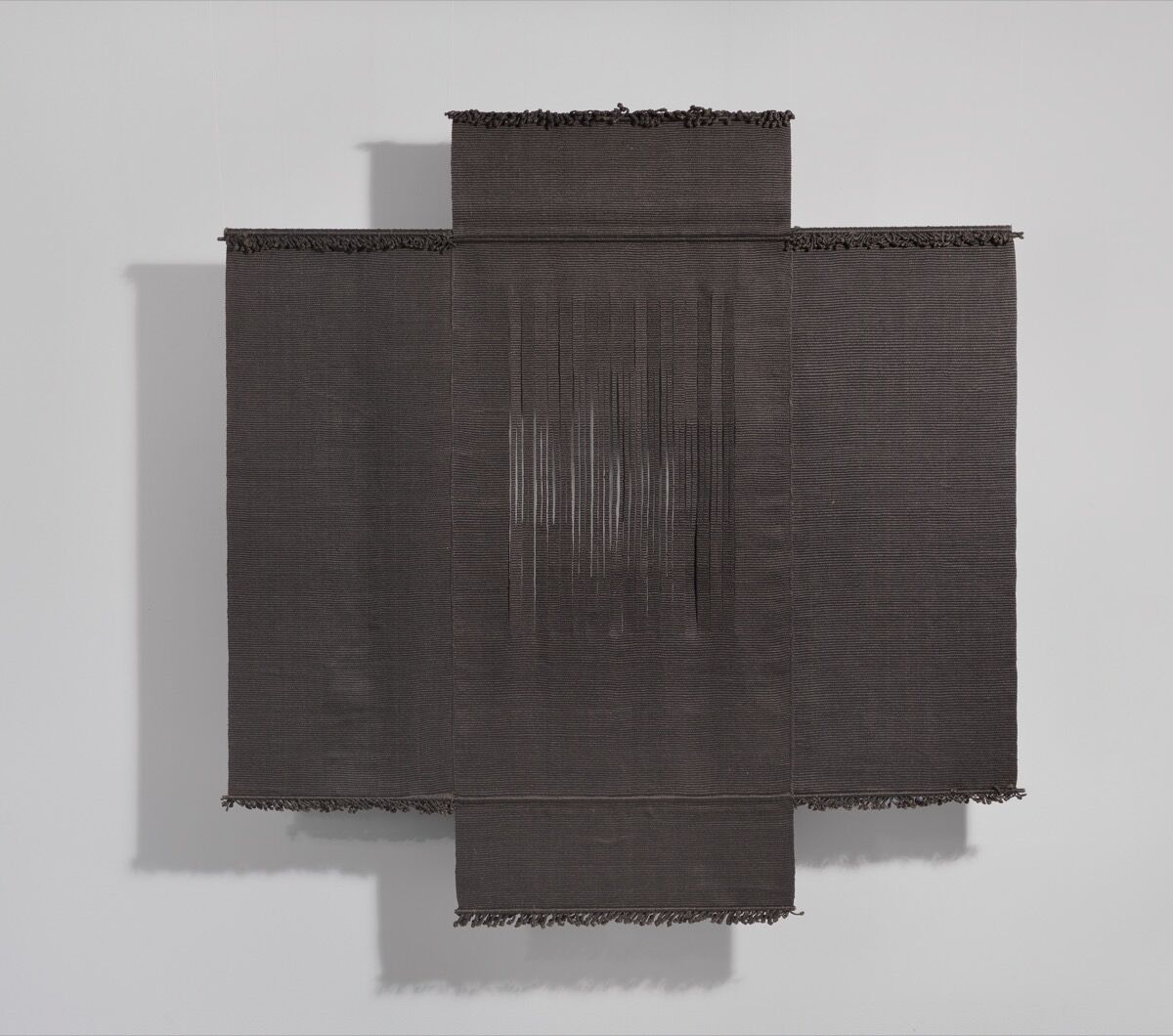

Meanwhile, down at the Whitney Museum, there is a whole floor devoted to craft. “Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019” casts a broad net over the museum’s permanent collection and comes up with a haul of interesting connections. There is Tawney, set alongside Agnes Martin, with whom she was strongly allied. The presence of figures like Richard Artschwager (who began his career as a furniture maker), Ree Morton, Alan Shields, and Harmony Hammond attests to the breadth of craft’s relevance in the 1960s and ’70s—precisely the time when the studio movement sought to forge links and was left disappointed. The finale is Liza Lou’s extraordinary Kitchen (1991–96), completed after five years of painstaking beadwork, a testament if ever there was one to the power of craft.