Source: Artnet.

Technology is no guarantee of market progress.

If you have even a single toenail touching this mortal coil, you’ve undoubtedly heard about NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and their potential to upend the art world as we know it. But trying to determine whether they will, let alone in what ways, demands doing what few buyers plunging into this emerging market want to do: dance with the devil in the details, starting from the foundation.

It’s helpful to think of NFTs as crypto-collectibles: tradable digital assets (in both the coding and investing senses of “assets”) whose authenticity, identity, ownership history, and sales prices are all tracked on a blockchain.

Like physical art and collectibles, NFTs are either unique or produced in limited editions. The “non-fungible” aspect comes from the fact that each NFT has a value independent of all others, including different editions of the same work, kind of like fine-art photographs or prints. “Token,” meanwhile, is a term of art for a unique alphanumeric code recorded on the blockchain. Like an inventory number or tracking code, the token locates the actual asset within a larger system.

That larger system, a blockchain, is essentially a database maintained by a distributed network of computers rather than a central authority such as a corporation or a government. The database consists of unalterable “blocks” of transactions, verified cooperatively by the network. The idea is that you can trust the system without having to trust any individual contributor.

Once data is “on-chain,” it cannot be deleted, and it can be reviewed forevermore by anyone with access privileges and enough technological know-how. This means each NFT’s scarcity and provenance are secure, which in turn amplifies demand, which in turn builds a more confident, more robust market than we’re used to seeing for digital artworks without blockchain backing.

Not so confusing, right?

Like any other technology, however, NFTs are much more complex than a decent elevator pitch can make them sound. Digging into the fine print exposes new possibilities and old pitfalls that will define their future.

Given the “chain” analogies, it’s fitting that the four issues below are all interlinked. On one hand, this imbues every individual factor with transformative potential; on the other, it also means that permanently anchoring any one of them will make the rest harder to alter, too. What happens from here will determine whether NFTs become a vehicle for generational progress in the art industry, or just another bubble with all-too-familiar contours.

Addie Wagenknecht, Sext (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

1. The Power of Gatekeepers

The Old Art World’s Problem:

People and institutions with long histories, fat pockets, and/or pre-existing industry connections wield enormous influence over who gets to participate in a fundamentally hierarchical system.

The NFT Difference:

New, decentralized marketplaces can welcome artists and buyers independent of the art establishment’s approval. While some NFT platforms (such as SuperRare and Nifty Gateway) will currently only accept artists by invitation or application, others (such as Rarible) allow any interested creator to start selling in their marketplace.

Ameer Suhayb Carter—an experienced designer and consultant in the crypto space gearing up to launch the Well Protocol, an NFT platform, archive, and support system with a special focus on BIPOC and LGBTQIA artists—represents the most revolutionary potential of the blockchain art space.

“In a lot of cases these are people who can’t even safely make work where they’re from. We’re giving voice to the voiceless,” Carter, who also works as an artist under the alias Sirsu, told Artnet News.

“The goal is to make sure they can build the communities they want to build as they see fit. I give them the tools to give them agency. I won’t build for you, I’ll build with you.”

The Roadblock to Revolution:

Yet decentralization is not always what it’s cracked up to be. As blockchain-fluent artist and developer Addie Wagenknecht told Artnet News: “The glitch is coming to terms with the mythology that distributed systems lead to disrupted power.”

While the crypto economy thrives on utopian rhetoric about freedom and democratization, she noted, the underlying technology is complicated for a layperson to even understand, let alone use on their own.

“Instead, what we are seeing unfold in real time is that complexity makes the majority of people buying and selling NFTs dependent on platforms,” she said.

Those platforms vastly simplify the process for users, but extract concessions—sometimes significant ones—in exchange.

“We have seen this a million times before,” Wagenknecht continued. “Facebook won because learning to host your own sites, chat clients, and blogs was too much work. So what is happening is the same people who disrupted banking or technology or the web in the Valley are now claiming that they have changed the world again, when really it’s just the same people making the same stuff for the same people to get rich from.”

What to Watch:

What matters now is how much of the NFT market consolidates on the most prominent marketplaces, and how many grassroots platforms can emerge and sustain themselves.

“You can’t rely on the technology, and things built on this technology, to be inclusive,” Carter added. “It takes human work and active choice. What we’re going to do as a community, as an organization, is be on the lookout, assist, and uplift when we can.”

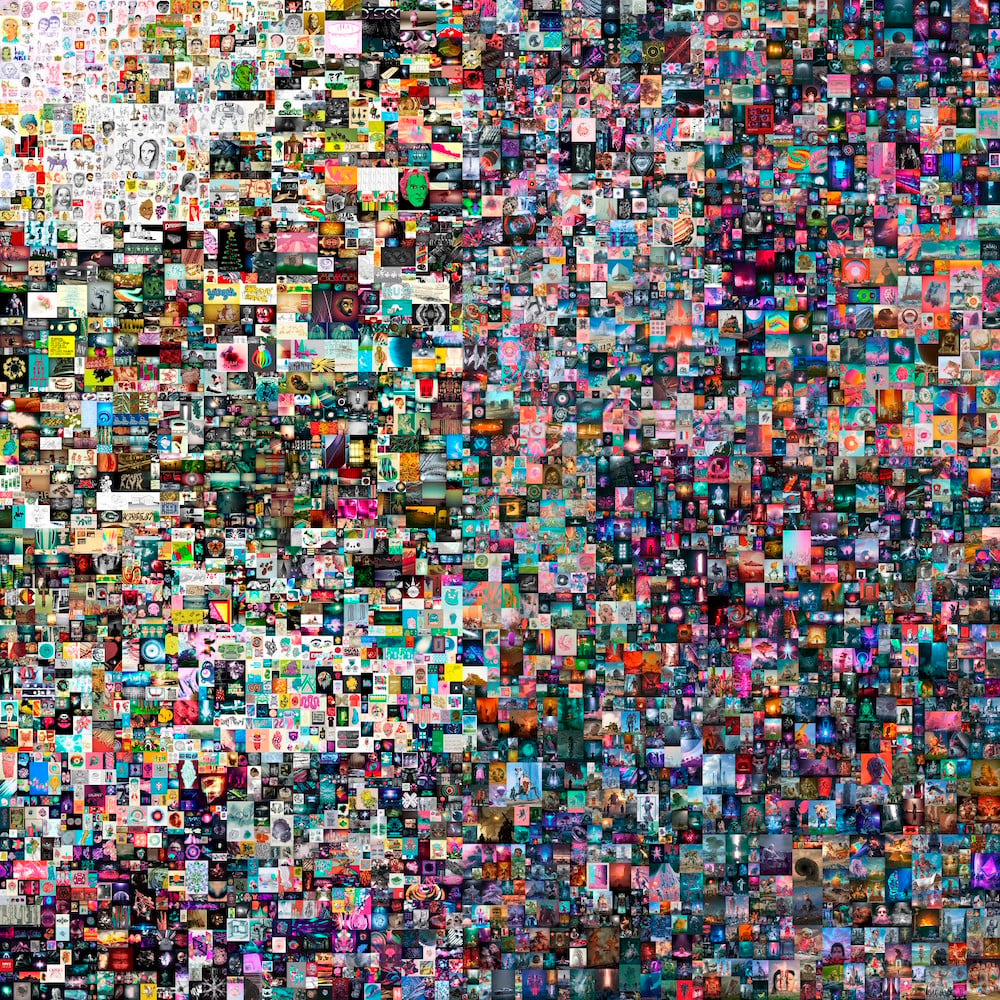

Beeple, Everydays – The First 5000 Days NFT, 21,069 pixels x 21,069 pixels (316,939,910 bytes). Image courtesy the artist and Christie’s.

2. The Values of Collectors

The Old Art World’s Problem:

Part of what makes established gatekeepers so powerful is the cyclical nature of upper-echelon art collecting. Dealers compete with dealers to represent the same kinds of artists that collectors want so desperately to buy: all too often, the artists that look like them, meaning people who are predominantly white and male, and have connections inside the high-art community.

The NFT Difference:

So far, many, if not most, NFT buyers hail from outside traditional art industry circles, and tend to have little interest in established dealers’, advisors’, and collectors’ opinions on what is worth acquiring—and at what price.

“The money coming into the space is money that was already in the space,” according to Kevin McCoy, the artist who created the first NFT as part of Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference in 2014. “Crypto people are buying NFTs. I’ve always thought that’s the strength: new makers and new collectors, not the old art world.”

The Roadblock to Revolution:

But here’s the thing: many, if not most, of the crypto-wealthy tend to look a lot like the traditionally wealthy—again, predominantly white and male. And while they may not care what art-world tastemakers think, their concept of merit is just as much of a feedback loop—this time, fixated on Silicon Valley idolatry and social-media stardom.

As Tina Rivers Ryan, an assistant curator at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and historian of video and digital art, put it: “Is an art market that clearly, openly, brazenly ties an artwork’s value to labor-intensive social networking accessible?”

Her question exposes the fault lines in the NFT marketplace. It’s true that Beeple (AKA Mike Winklemann) had no chance of selling his NFT work for $6.6 million through Gagosian or Sandy Heller despite his 1.9 million Instagram followers. But this isn’t the type of inclusivity most urgently needed in the traditional art industry.

What to Watch:

“What I’ve seen happening the last year is NFTs selling into the millions, showing us in real time what disaffected white bros trafficking in meme culture looks like,” Wagenknecht said. If this activity continues dominating the headlines and the marketplaces by year’s end, it would be a troubling sign.

Bria Thomas, Flower From the King’s Meadow (2020). Courtesy of the Mint Fund.

3. Redistribution of Wealth

The Old Art World’s Problem:

When it comes to cashing in on art, nearly all the major upside accrues strictly to the collector on resale. Even the most fortunate artists generally only receive, at best, a meager resale royalty. The UK, for example, caps resale royalty for its residents at €12,500 (about $17,300), no matter how much money a work fetches when it returns to market; the US offers no resale royalty at all—at least, outside of sales made during a one-year period in California in the late 1970s.

The NFT Difference:

Artists have the potential to benefit proportionally and perpetually as their works circulate through the marketplace over time, because percentage-based resale royalties can be baked into the terms of every NFT sale.

Perhaps best of all, this redistributive function can be entirely automated. Why? Because the underlying mechanism of NFT trades is the “smart contract,” a set of commands that executes on the blockchain without human intervention once objectively verifiable conditions are met. (Hypothetically, say, “ownership of this asset transfers to the sender as soon as the sales price reaches the current owner’s account.”)

To Amy Whitaker, a professor of visual arts administration at New York University who began researching blockchain in 2014, the possibilities become especially fascinating when NFT artists use smart contracts to redistribute wealth to more than just themselves.

Artist Sara Ludy, for example, recently negotiated a novel sales split with her New York gallery, bitforms, for any upcoming NFT works: 50 percent for Ludy, 15 percent to the NFT platform, and 35 percent to bitforms—with that last figure evenly divided in seven percent increments between the gallery’s owner and four staff members.

Whitaker analogized this move to a tip pool for restaurant workers. It’s a means of “collectivizing economics” and, if the artists choose, even “combining for-profit and nonprofit structures so people can funnel some of the proceeds into grantmaking or charity” without needing to fill out additional tax forms.

The Roadblock to Revolution:

When it comes to resale royalties, McCoy cautioned that there is a gap between the “utopian possibilities” of NFTs and much of the current reality.

By and large, artists are still using a standard Ethereum smart contract (known as ERC-721) with no resale redistribution component at all, while—true to Wagenknecht’s warning—each platform dictates its own resale royalty limits.

What to Watch:

In McCoy’s view, this pattern needs to be inverted, with NFT artists working together to reinvent resale royalties, marketplace structures, and even exhibition design in ways that prioritize their own needs.

Carter provides reason for optimism. Aside from the Well, he is also a cofounder of the Mint Fund, a grassroots organization that provides crowdfunding and community support to artists—especially BIPOC and LGBTQIA outside North America and Europe—looking to produce their first NFTs. (To “mint” means to register an artwork on a blockchain so that it can be offered for sale.)

Buying and selling through the Mint Fund gives users the option to donate part of the proceeds back to the organization via the blockchain, in an effort to create “generational and circular economic structures” for “every artist, whether they’re making $200 or $2 million consistently.”

Between its Twitter account and Discord channel, the Mint Fund currently has about 3,600 community members. It also just onboarded 35 artists out of its first round of applications, and Carter said it is receiving “hundreds more applications every couple of weeks.”

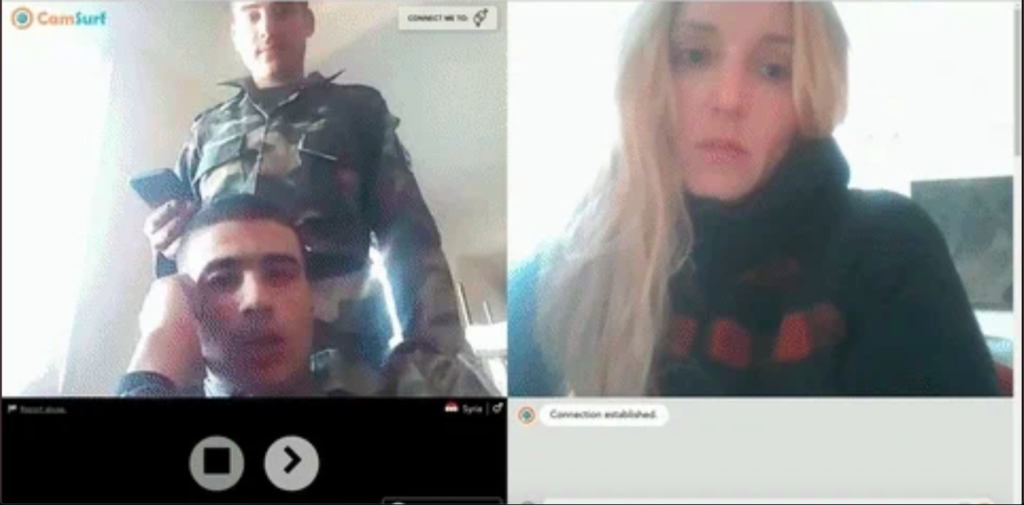

Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, Still from Public Key / Private Key, 2019. Image courtesy of the artists.

4. Ownership and Preservation

The Old Art World’s Problem:

Beyond traditional tangible media, ownership of (and copyright to) artworks such as installation, performance, and video often descend into a marsh of confusion.

Dealers and artists must generate term sheets for each work from scratch, with the resulting documents normally whipsawing between overly simplistic and maddeningly complex—all for the collector to frequently misunderstand or ignore their responsibilities, especially concerning the work’s long-term care.

The NFT Difference:

The blockchain contains the work’s complete provenance and copyright details, with the potential to add a wide range of surrounding information that could benefit historians and archivists. Standard contracts like ERC-721 are available for wide use by artists unsettled by the prospect of drafting their own agreements. Should intellectual property disputes arise, an NFT’s full transaction history can be audited all the way back to its minting, providing unassailable “on-chain” proof of which party’s claims are legitimate.

The Roadblock to Revolution:

Glossed over in most descriptions of NFTs is a crucial fact: what lives on the blockchain is data describing and tracking the asset, not necessarily the asset itself.

Remember, the token is basically just an inventory number. It links to an artwork, but in what McCoy called “the vast majority” of cases, the artwork is hosted off-chain somewhere else. This setup raises a horde of uncertainties about ownership, copyright, and preservation that many NFT participants are unaware of unless they painstakingly pore over the terms and conditions.

For example, if an animated GIF is actually stored on a server controlled by the marketplace where you acquired its NFT, do you own the GIF… or just a license to access it? Either way, what happens if the marketplace eventually goes out of business or sells to another company?

“There’s a question around the permanence of the media, the conservation and archival issues around that,” McCoy said. “Of course, almost no one is worrying about that now in this ‘go go go’ moment.”

McCoy experienced this friction directly during the lifecycle of Monegraph, the NFT platform he iterated with Anil Dash at Rhizome almost seven years ago. “The original Seven on Seven work in 2014 was very much how NFTs work now: If you own this blockchain entry, you own the work,” he explained.

But when the Monegraph marketplace opened for business, attorneys pushed it to become “much more licensing-oriented” through complex agreements and terms of service that pushed it away from its original intent.

What to Watch:

Monegraph’s evolution illustrates the tension between “the underspecified, crypto-native, YOLO approach, and the overdetermined, legalistic, less exciting approach” to NFT ownership, McCoy said.

He judges that the market is currently still operating much closer to the former than the latter, but that it will be important to see if and when that shifts.

Addie Wagenknecht, There Are No Girls on the Internet, 2020. Courtesy of GIPHY.

Summing Up

The four issues above are hardly the only ones that will determine the transformative impact of NFTs. Take environmental impact. The vast majority of existing platforms run on the Ethereum blockchain, which by some estimates now matches the annual energy burn of Ecuador; a coalition of artists (including Wagenknecht) recently collaborated to produce A Guide to Eco-Friendly Crypto Art, but it remains to be seen how many platforms and participants will heed the call.

Back on the operational level, smart contracts may or may not be enforceable in an offline court of law. Even if they are, it’s unclear how unalterable, but nevertheless problematic, blockchain records could be corrected—a major concern if an artist, say, finds their work and/or identity have been appropriated into NFTs and dealt without their authorization.

It’s even possible that crypto isn’t the optimal technology for addressing these inequities. For Carter, the potential energy comes much less from the specific capabilities of blockchain than from the way interest in NFTs has galvanized people to radically restructure how the art market could work if they started from square one. Because in a way, they can.

“A lot of people say, ‘Oh it’s early,’” he said. “But by being first and being early, we have a responsibility.”

“If you want to set a precedent where people respect the space, the artists, the medium, then we have to come at it with generational forward thinking,” he added. “I’m urging people to start thinking about intentionality and being actively present in this moment. Because when it’s gone, it’s gone.”