Source: Artsy.

The New York based art historian and global head of the UBS Art Collection, explores the diverse and impactful shifts in the art world that have taken place in less than a decade. These include the normalization of art as a financial investment, the global proliferation of private museums, and the blurring of traditional roles for auction houses and art galleries, to name just a few.

In the six years since Mary Rozell, global head of the UBS Art Collection, published the first edition of The Art Collector’s Handbook: The Definitive Guide to Acquiring and Owning Art (2014), the art world, for all its insularity and status quo–driven tendencies, has changed.

The shifts that have taken place in less than a decade are diverse and impactful, including the normalization of art as a financial investment, the global proliferation of private museums, and the blurring of traditional roles for auction houses and art galleries, to name just a few.

Rozell, a New York–based art lawyer and art historian, is releasing a revised edition of The Art Collector’s Handbook on October 5th in an effort to capture these changes. The forthcoming edition will include updates across every section and an entirely new chapter.

Accepting art as an investment

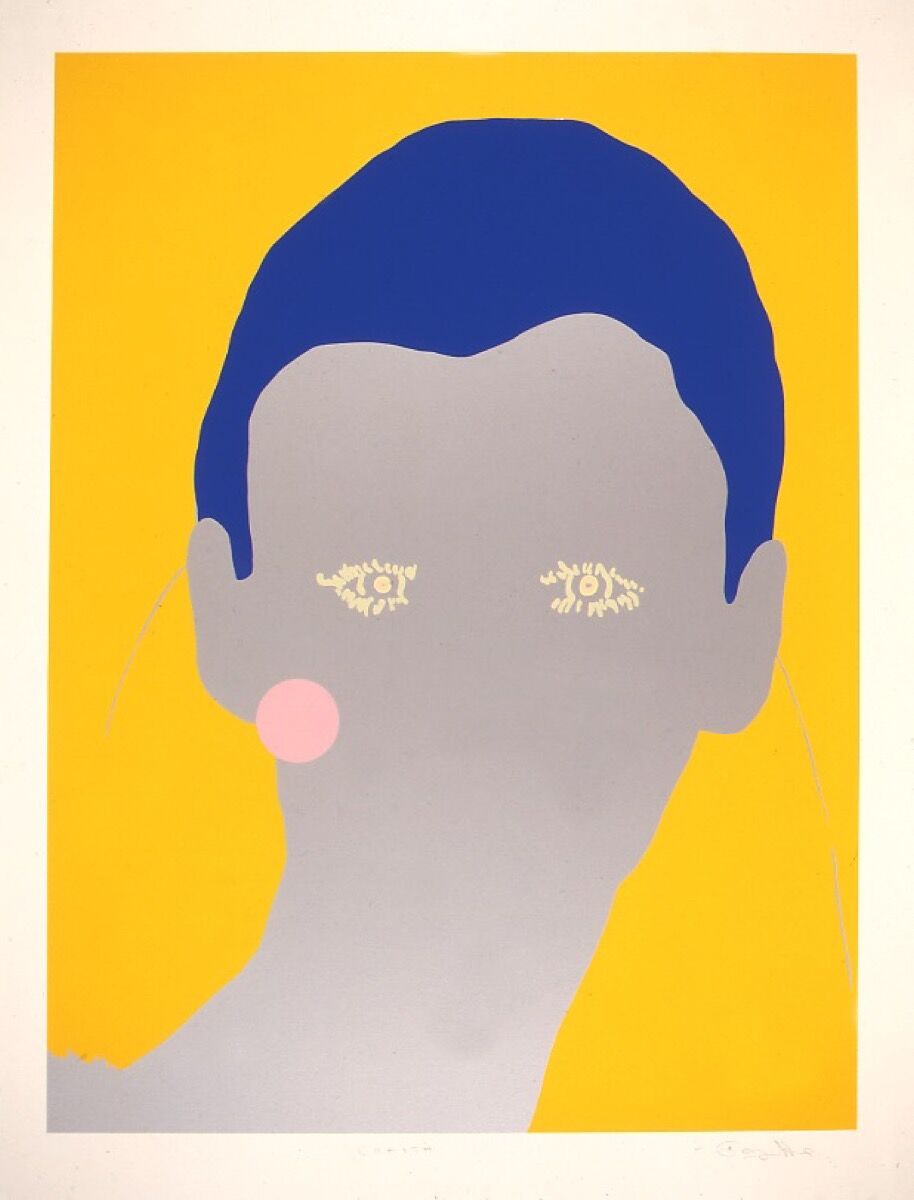

Mindy Shapero, Night Pieces, The lost unseeing eye, 2013–18. © Mindy Shapero. Courtesy of the UBS Art Collection.

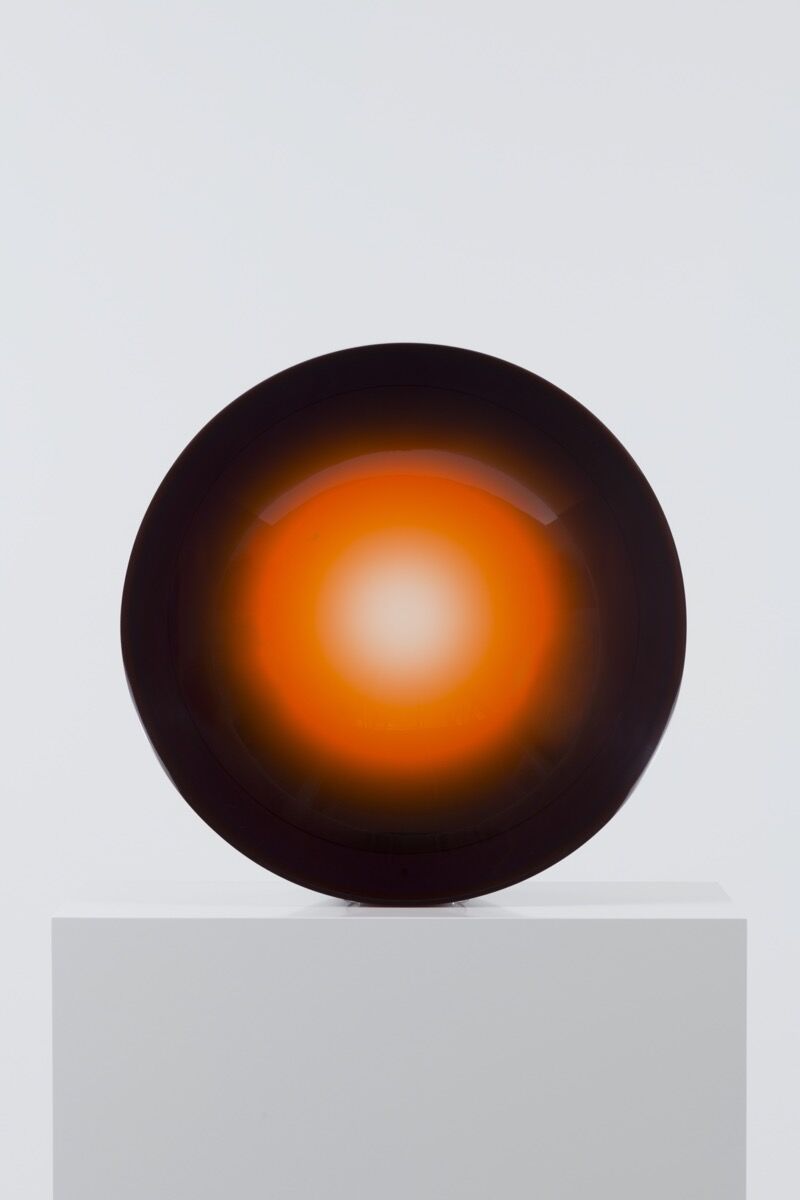

Fred Eversley, Untitled (parabolic lens), (1969) 2018. © Fred Eversley. Photo by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery and the UBS Art Collection.

Speaking to Artsy over the phone about what she considers to be one of the more notable shifts, Rozell said, “Ten years ago when people were talking about artists and investments, a lot of people were upset about it. Every art fair had a lot of panels and this was the number-one topic. There was a lot of pushback, but now it has become accepted and institutionalized that art investing takes place. There are more forms and vehicles to invest in art, with all the same caveats, but it’s become more of the norm.”

An aspect of the financialization of the art market which Rozell finds intriguing is the controversial third-party auction guarantees that typically ensure a work is pre-sold at a minimum amount, backed by an auction house (known as house guarantee) or a third-party guarantor who receives some money should the work sell for more.

“After the crash of 2008, third-party auction guarantees all but disappeared, and now they are very much back supporting the art market, up to 40% in 2017 with 90% coming from outside third parties who saw potential investment,” Rozell said. “Auction houses do approach collectors and invite them to be third-party guarantors, so that has proven to be a means to offer sellers a degree of comfort and buyers investing in potential opportunities.”

Art industry roles become blurry

Mary Rozell in conversation with Ed Ruscha at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Photo by David Parry. Courtesy of UBS Art Collection.

Rozell, who is also the former director of art business at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art in New York, pointed out that there have been continued and rapid shifts in the very structures of the art market, with a blurring of the traditional roles of auction houses and art galleries.

“People forget that it was unheard of not long ago [for] people who would work at an auction house to go and work at a gallery and vice versa—you would stay in your lane, kind of like how there were no contracts, it was more of an understanding because there could be potential conflicts of interests and information sharing,” she said.

According to Rozell, auction houses are behaving more and more like art galleries. In particular, private advisory services and private dealing—which represent a big part of business at Sotheby’s—are encroaching on gallery territory.

Gary Hume, Cerith from the “Portraits” portfolio, 1998. © Gary Hume. Courtesy of the artist, The Paragon Press London, and the UBS Art Collection.

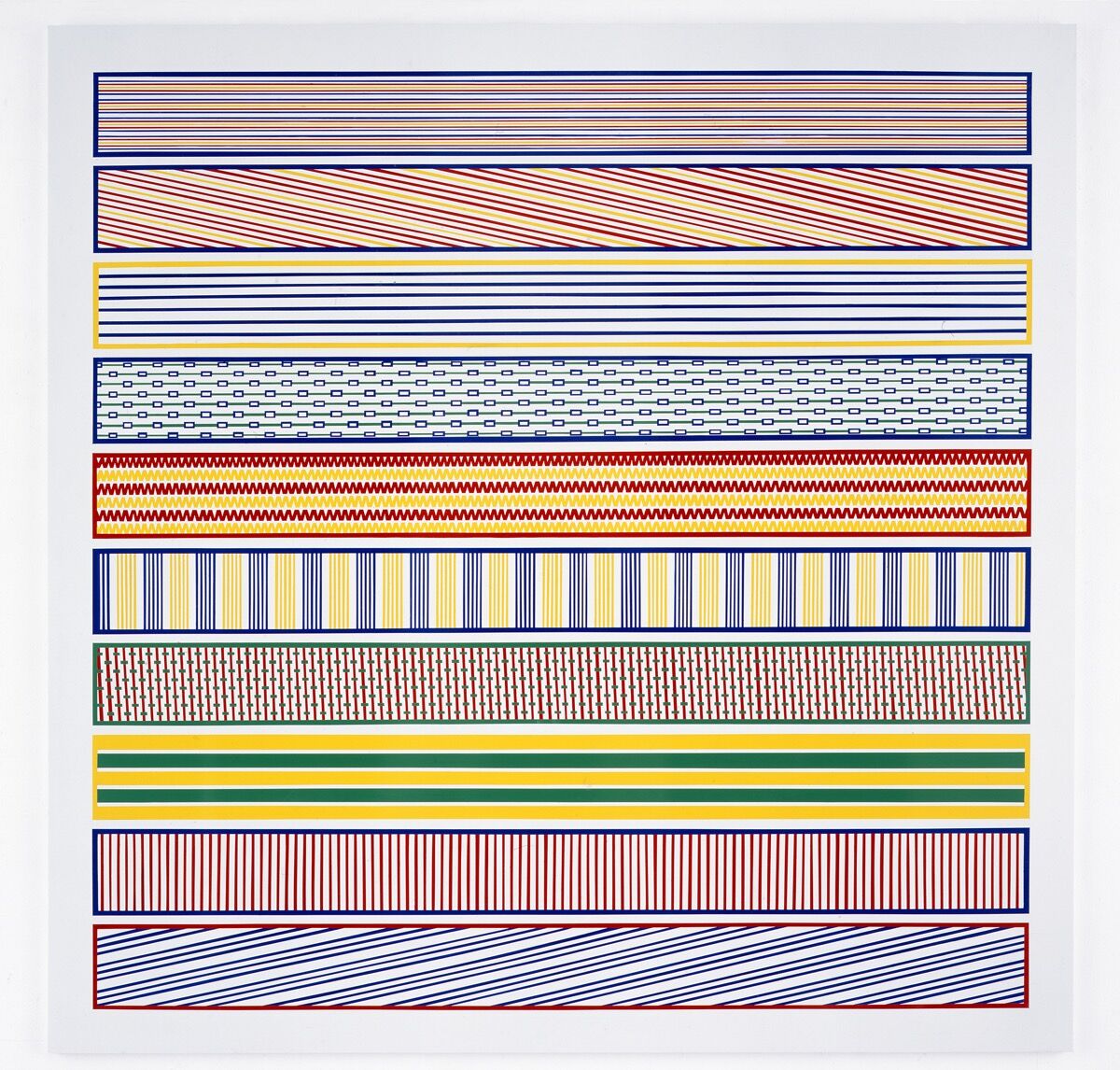

Angus Fairhurst, 3rd Lowest Expectations, 1996. © The Angus Fairhurst Estate. Courtesy of Sadie Coles HQ and the UBS Art Collection.

She also cited the recent example of three top art galleries, Pace, Gagosian, and Acquavella, collaborating to jointly sell the approximately $450 million collection of the late philanthropist Donald Marron. The announcement in February this year shocked the art world, as it was expected that either Christie’s or Sotheby’s would manage the sale of the estate. Instead, the collection—which includes major artworks by Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko, and Cy Twombly, amassed over 60 years—will be shown at Gagosian’s and Pace’s Chelsea galleries next year. Earlier this summer, around 40 works on paper from the collection were on show at Pace’s new space in East Hampton, New York.

Rozell said the Marron estate going to galleries reflects another trend in the art market: the melding of power at the top, specifically among mega-galleries. “It is the consolidation of power that these big galleries can do,” she said, “and when you go to places like the Hauser & Wirth complex in L.A. with [its] restaurant and bookstore, or you go to the new Pace tower in Chelsea, [you can see] these are very different spaces that represent this shift in power, which is interesting.”

The shift to digital

Shinique Smith, Bale Variant No.0025 (Good & Plenty), 2019. © Shinique Smith. Photo by Dan Tuffs. Courtesy of the UBS Art Collection.

Shinique Smith, And there you are, a shooting star, 2018. © Shinique Smith. Courtesy of the UBS Art Collection.

When looking at the changes in the art world over the past six years, discussing advancements in technology is unavoidable. Rozell pointed out the following developments that have come with improvements to technology since the first edition of The Art Collector’s Handbook: new modes of creating art, an entire parallel universe of virtual-reality art, the first painting created by artificial intelligence auctioned at Christie’s, and the introduction of blockchain technology.

The art world’s increased adoption of technology has, of course, become incredibly important when looking at the ongoing pandemic and its impact on the art industry. Since March of this year, the art world has undertaken widespread efforts to go digital during a time of international travel restrictions and social precautionary measures. Rozell does not find this development surprising, seeing the current push towards digital as an acceleration of a move that was already in the works. She cited David Zwirner’s online viewing rooms launched in 2017 as an example—something it was able to pull off as a high-end gallery with the resources, but also compelling mid-level players to focus on their digital offerings as well.

However, Rozell does not think the digital realm will replace existing physical practices. “I don’t think anybody, not even the art fairs themselves, believe that the digital is an adequate replacement for seeing art in person,” she said. “Art by its very nature is meant to be interactive, and it’s very personal.”

Moving to a more diverse art market

Federico Herrero, Untitled, 2019. © Federico Herrero and Sies + Ho?ke, Du?sseldorf. Courtesy of the UBS Art Collection.

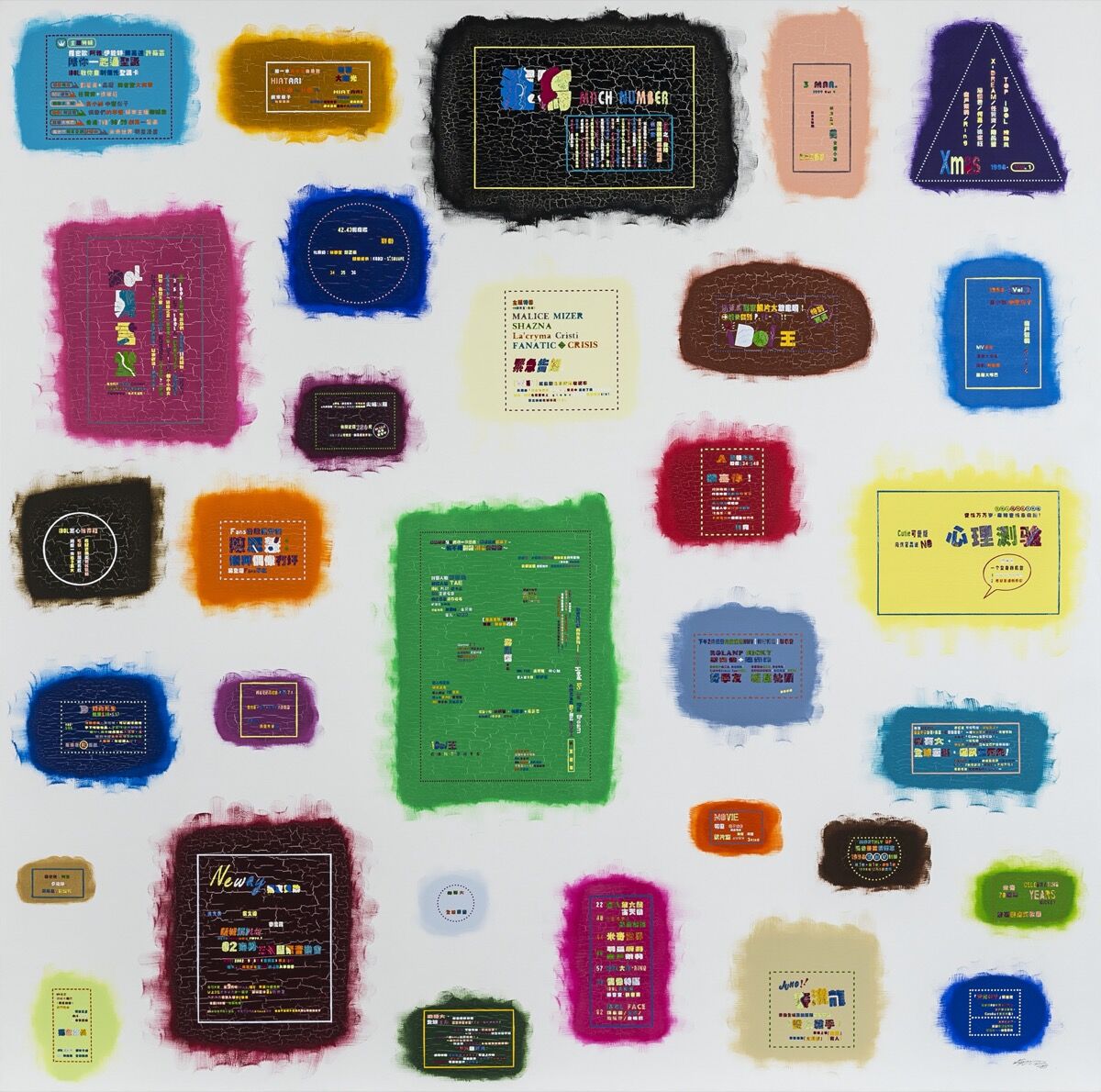

Zheng Guogu, Computer Controlled by Pig’s Brain 2014 No. 2, 2014. © Zheng Guogu. Courtesy of the artist, Vitamin Creative Space, and the UBS Art Collection.

Reflecting on the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement and recent online protests regarding racism in the art world, Rozell said there is a growing consciousness about the imbalance in art collections.

“I saw this at UBS when I started five years ago. I noticed that it was very white and very Western, and we are a global bank, and that needed to change. I don’t think it’s a moral failing, but it’s a reflection of what was on the art market itself—it is very clear so many artists were overlooked,” Rozell said.

“Sam Gilliam is a great example,” she continued. “When he first started creating art, he was as big as Jackson Pollock, and then he kind of became almost more of a regional artist in Washington, D.C., where I worked at the time, and then people realized, ‘Oh my God, he was an amazing artist,’ and then his market takes off. We see this happening all over. This applies to women, too; women have not been well represented in the art market.”

According to Rozell, another change impacting art collecting currently is the rise in female wealth creation in the world. “Women billionaires are growing at a higher rate than men,” she said. “As more and more women control global wealth, it is going to impact the art market. UBS did a study on high-net-worth collectors, and women spend more money collecting art than men, so there is more female purchasing power, and that is going to shape the future of the art market.”

“I wish these shifts would happen faster,” she added, wistfully.

Reena Devi