Source: The Guardian.

The social media platform was once a favourite of artists and photographers, but a shift towards TikTok-type videos and shopping could leave them looking for a new home online.

In late July, hobbyist photographer and self-proclaimed “sunrise hunter” Sam Binding conducted an experiment. After visiting Somerset Lavender Farm to catch the sun peeking over the purple blossoms, the 40-year-old from Bristol uploaded the results to both Instagram and Twitter. Two days later, he used the apps’ built-in analytics tools to assess the impact of his shots. On Instagram, a total of 5,595 people saw his post – just over half of his 11,000 followers. On Twitter, his post was seen by 5,611 people, despite the fact he has just 333 followers on the site.

This confirmed Binding’s hunch that although most people believe that Instagram is a place to share photos and Twitter is a place to share words, that may no longer be the case. When it launched in 2010, Instagram courted the artistic community, inviting respected designers to be among its initial users and naming its very first filter X-Pro II, after an analogue photo-developing technique. In her 2020 book No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, technology reporter Sarah Frier documents how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom wanted Instagram to be an outlet for artists (in a high-school essay, Systrom wrote that he liked how photography could “inspire others to look at the world in a new way”).

Instagram head Adam Mosseri: ‘The number one reason people say that they use Instagram is to be entertained.’ Photograph: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for Wired

But Facebook bought Instagram in 2012. Systrom departed as CEO in 2018. And three weeks before Binding uploaded his lavender pics, the new head of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, posted a video to his personal social media accounts. “I want to start by saying we’re no longer a photo-sharing app.”

Click on Instagram today and you will still see plenty of photos, but you’ll also be confronted with a carousel of short, vertical videos (known as “Reels”) as well as the more-than-occasional ad. In his video, Mosseri explained that “the number one reason people say that they use Instagram in research is to be entertained” and the app was going to “lean into that trend” by experimenting with video. Citing TikTok and YouTube as competition, Mosseri said Instagram would “embrace video” and users could expect a number of changes in the coming months.

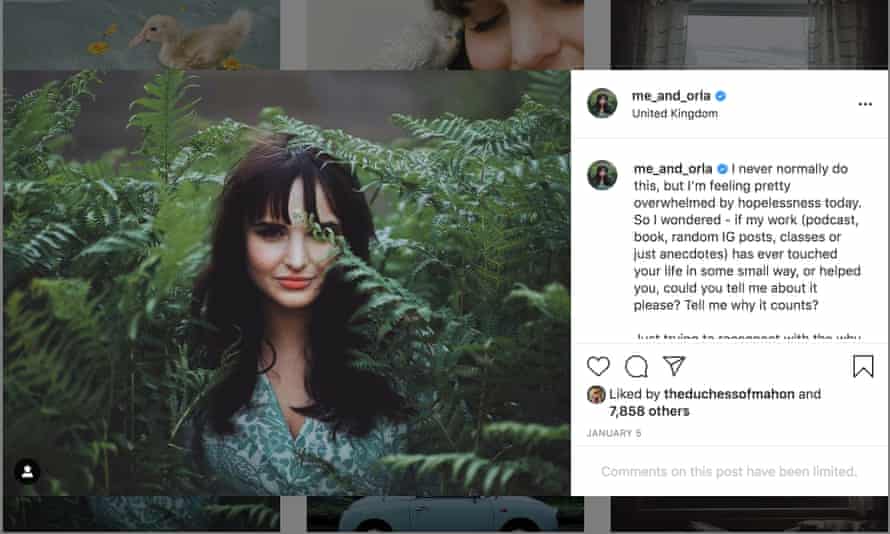

The move has the artistic community seeing Pantone 032. Though there’s no way of knowing how many artists, architects and photographers have left the app, many are at least threatening to. Liverpool photographer and musician Reuben Wu tweeted “Ok thx bye Instagram!” on hearing the news (at the time of writing, he and his 264,000 followers remain on the app). Sara Tasker, an Instagram and creative business coach and author of Hashtag Authentic: Finding Creativity and Building a Community on Instagram and Beyond, says her inbox was “immediately flooded” with creatives “terrified that this meant they would be left behind”. The 37-year-old says video is time-consuming, has a steeper learning curve and can be a challenge for those who are self-conscious in front of the camera.

Sara Tasker: ‘The idea that they have to dance for their audience – literally – just to make sales or have their art seen is a kick in the teeth.’ Photograph: @me_and_orla/Instagram

Binding started sharing sunset photos on his account @sambinding around five years ago and he now sells pictures to those who message him on the site. But over the past year, Instagram has begun showing his posts to 30-50% fewer people and he’s consequently made fewer sales. (In November 2020, Instagram altered its layout to highlight Reels and its Shopping features.)

Artist and photographer Nick Waplington is also troubled by changes at Instagram, which he has used for 10 years. The 56-year-old has 18,000 followers on his @nickwaplington account, through which he regularly sells limited edition artworks and monographs. “I’m not going to start dancing around holding my photographs,” he says. “I’ll probably go back to using it as a personal account now.”

Like Binding, Waplington’s reach has recently decreased: “I used to put on 100-200 new followers every month and that’s ended,” he says. Also, like Binding, Waplington has been driven to experiment. He recently uploaded a photo of model Kendall Jenner that he lifted from the web. “It really went nuts. I got the most likes and the most reach that I’d ever had. They showed it to everyone.”

In 2020, the non-profit research organisation AlgorithmWatch conducted a similar experiment. In partnership with the European Data Journalism Network, it analysed 2,400 images and found that photos of women in underwear or bikinis were 54% more likely to appear on the Instagram news feed than other photos, while images of food and landscapes were 60% less likely to be shown. While the experiment was small, relying on the feeds of 26 volunteers, the researchers concluded that “refusing to show body parts dramatically curtails one’s audience” on Instagram. In a June 2021 blog post, Mosseri outlined how users can influence what they see by muting accounts or clicking “Not Interested” on particular posts.

Nick Waplington: ‘Do they really want someone like me to be posting pictures of celebrities downloaded from the internet to increase your reach instead of posting my art?’ Photograph: @nickwaplington/Instagram

Ironically, Mosseri started his announcement video by claiming that Instagram wants to empower creators to “make a living” on the site, but both Binding and Waplington have seen sales suffer. Perhaps this highlights the difference between “creators” and “creatives”. In April, writer and Washington University media professor Ian Bogost argued that “a creator is someone whose work is wholly circumscribed by a platform”. While creators make content that can only exist within a certain app, many creatives simply put their offline art online. To put it another way: Instagram’s creators can only exist on Instagram, Instagram’s creatives can go elsewhere.

“There seems to be a mass exodus to Twitter now,” Binding says. VSCO, a photo app reminiscent of early Instagram, is popular with Gen-Z and currently has around 40 million monthly users, meaning it’s well placed to attract Instagram migrants. Artists are also turning to social media sites such as Artfol, ArtStation and Bubblehouse, which are all specifically designed for creatives to showcase their work. This isn’t the first time Instagram has angered the artistic community – in 2019, American artist Betty Tompkins was temporarily blocked after she shared her explicit photorealist work Fuck Painting #1, leading hundreds of people and the galleries that host her work to complain to the site. (Instagram has a long-held reputation for censoring artistic nudity, which is ironic in light of AlgorithmWatch’s discovery of the bikini bias.)

Still, Brench admits she feels “a bit chained” to Instagram and doesn’t want to completely quit the site because of the community there (she mentors young artists via the app). Waplington also values the community on the site. “I’ve been making art photography for a long time and you would go away for four or five years and exist in this vacuum while you made a new piece of work,” he says. “For a line of work where it’s very insular, suddenly you were able to talk to people on a daily basis.”

And yet, like many in the artistic community, Brench says Instagram has negatively affected her work – and her attitude to her work – over the years. “I drew some pictures of some cats and I’m not even a cat person whatsoever – I actually hate cats. But I posted it on Instagram and I knew it would do really well,” she says. The post did do well. “But then I thought, ‘That’s not me.’”

So, this time next year, will Instagram be solely a video and shopping app, full of dancing creators and celebrities flogging merchandise but devoid of artists and designers sharing their latest work? It’s likely that many artists will stay on the app and adapt – Binding, for one, says he doesn’t mind creating videos – and it’s possible that Instagram will change its stance. After all, Facebook has found, time and time again, that copying competitors isn’t a quick and easy path to success – last year, it shutdown it’s two-year-old TikTok clone Lasso, which never earned more than 80,000 daily active users on Android.

Taaryn Brench: ‘You hear people talking about fighting the algorithm but that’s a job in itself.’ Photograph: @taaryn_b/Instagram

Whatever happens next, it’s clear that Instagram isn’t the app it used to be. Instagram expert Tasker says it once nurtured creators with workshops, parties and even surprise gifts such as photobooks and calendars, which she says is no longer the case. Instagram employs people who curate content for its own official account so it arguably fosters talent in that way – its latest post highlights the work of trans activist and spoken word poet Kai-Isaiah Jamal.

In an emailed statement, a Facebook company spokesperson wrote: “We’re inspired by the millions of creatives using Instagram to express themselves, create businesses and communities every day. We began as a photo-sharing app and will always be a platform for visual storytelling, no matter its format.” They went on to say that Instagram users shape culture and the app is “constantly developing new formats and tools to help people express themselves”.

Tasker first found Instagram seven years ago when “lonely and lost” on maternity leave; she was delighted to be connected to others who “found beauty in the way the light shone on their kitchen table in the early dawn” and “spotted the same tangle of wildflowers in the pavement cracks that would catch my eye”. Now she fears Instagram execs are “sacrificing longevity and real human connection for happy shareholders and panicked, short-term gain”.

While she feels that creatives will remain on Instagram (“there isn’t anywhere else online right now that has the same range and depth of creatives in its daily active user base”), she misses the place it used to be. “Open the app now and you’re grabbed by flashy images, videos, dancing teenagers and curated performances tailored, algorithmically, to hotwire all of your brain’s most basic likes,” she says. “It’s entertaining, there’s no doubt, but it’s seldom mindful. I miss that morning routine of quiet, considered and consistent inspiration.”