Source: The Guardian.

After Covid forced galleries to move their exhibitions to a digital space, artists and art institutions are now grappling with a divisive new normal.

Walking into Canada Gallery on the Lower East Side, a wall of 400 latex masks greets you. The faces express frustration and weariness.

Michael Mahalchick’s seventh solo exhibition, US, represents Donald Trump’s “basket of deplorables”, a phrase Hillary Clinton used to describe of Trump supporters during his 2016 presidential campaign.

The show was created in 2018 but presented to a 2021 audience, as viewers are able to see the masks in person, a luxury stripped just a year ago when gallerists found themselves scurrying to adapt to a digital model at the height of lockdowns. And as New York City climbs out of the pandemic era, the art scene continues to adapt to a hybrid form of digital and limited in-person experiences.

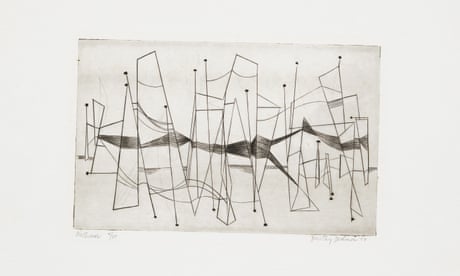

‘Museums overlooked these artists’: celebrating the forgotten women of abstract art

Last year, when Covid-19 left galleries with highly restricted access and 61% of all global art fairs were canceled, the market was forced to evolve digitally. Physically experiencing art was no longer a prerequisite to purchase or enjoy works.

For some galleries, the growth of online viewing rooms remains exciting and brings respite from time-consuming global fairs. Yet, others are conflicted on whether digitalization is eroding the physical power of art and abandoning the community.

With one of the world’s largest bases of high-net-worth and upper-middle-income wealth, New York City’s 1,500 galleries are the heart of the art industry: 90% of the nation’s art sales take place here.

Whitney Museum Of American Art in New York City. Photograph: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

And like most industries, the art market took a hit in 2020, with sales falling by 22% to $50bn. But this downturn was nothing like the 2009 financial crash that saw the market shrink by more than a third. With the market bouncing back, some attribute this growth to the mega-rich, with America’s billionaires increasing their wealth by 62% in the past year. Still, many argue that technology, not the rich, has been the market’s savior.

Last March, as the pandemic inundated the nation, Canada was quick to pivot.

“It was second nature,” said Phil Grauer, the gallery’s co-founder, to the Guardian. Because of a pre-existing database of images, online exhibitions opened fast. “We had young people staffing the place that could help us with building online viewing rooms,” he says.

Coming out of the pandemic, the gallery still uses online showrooms to generate international sales, reaching collectors who may never have had the opportunity to set foot in the Lower East Side space. They can cover more ground than before. “Online rooms sort of revolutionized the moment,” Grauer adds.

Last month, a sign of the art market’s revival brought hope for Grauer and his team. The Armory Show was back in hybrid form.

The art fair was the first major American show to take place since the pandemic. Still, more than 50 galleries outside the country could not make the trip to New York due to international Covid protocols. So even in the physical art fair, many works had to be displayed in online viewing rooms.

At the show, Grauer wasn’t rushing back to his booth. Art fairs going digital lessened the day-to-day pressures of running a gallery. From the Venice Biennale to Miami Basel, before Covid, Grauer was expected to ship artworks across continents regularly to showcase at fairs. “Finally, this madness has subsided,” he says. “There was a momentary sense of real relief – we can catch our breath and still survive in this other manner.”

The Armory Show in September. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

“The online viewing room is the most ridiculous notion of technology,” said Sebastian Errazuriz, a New York City-based artist and designer known for “vandalizing” Jeff Koons’s augmented reality Snapchat sculpture. “It’s basically just a website with a jpeg on it.”

He adds that galleries should offer to scan 3D works and allow their clients to see life-size art in augmented reality in their own space. “If we’re thinking of film, journalism or music, they’re all industries that have been completely disrupted by technology.” Until gallerists invest in cutting-edge technology that truly bring artworks to life, Errazuriz believes galleries are simply “rephrasing their marketing” with online viewing rooms.

Oliver Miro is looking to lead this disruption. Last May, he founded Vortic, a virtual reality platform for galleries to curate shows and collectors to shop. “We were able to present exhibitions on the platform that were canceled in the real world,” Miro said, and “conceive exhibitions that may never have existed were it not for the software”. Miro’s resident gallery, Victoria Miro, had an “incredibly strong” 2020 because of sales through Vortic.

“There is something incredibly powerful about having moments of contemplation with masterpieces in your own time and without the crowds you may find in museums,” Miro adds. Online viewing allows collectors, curators and wider audiences to sit in front of an artwork and spend time experiencing and thinking about the work for as long as they desire.

Errazuriz disagrees. He believes digitalization is going to permanently undermine the role of gallery-as-gatekeeper in years to come. “People are buying apartments during Covid without having ever seen them, or they’re buying cars online,” he said. “Why do I need to go to a physical gallery? The traditional balance between galleries and artists that we used to see is also being disrupted.”

Sebastian Errazuriz in front of his video art installation A Pause in the City That Never Sleeps, which was projected on screens in Times Square in 2015. Photograph: Carlo Allegri/REUTERS

As a small and local gallery that opened in late 2019, Gbedemah did not have the resources to invest in sophisticated VR/AR technology. During the four months between March and July when the gallery was closed last year, Gbedemah left the gallery’s lights on 24 hours a day, displaying 40 pieces of art for the community to enjoy through the windows.

“People would [gesture] hugs through the window,” he remembered. “They were very supportive. They liked to escape to the world of visual art.”

By reaching out to many artists and friends of the gallery, “the very first day we reopened, one of our neighbors upstairs came down and bought a work for $3,000”, Gbedemah said. The gallery’s exhibition of Gabrielle Baker opened last month, and six pieces sold in less than two weeks.

Only 1% of New York City’s galleries are Black-owned. For Gbedemah, an immigrant from Togo who showcases art representative of the African diaspora, this comes with greater responsibility and privilege, “even when it’s a burden to keep the lights on”, he said. “Most of our clientele are local people, and we consider ourselves a community gallery,” he said. For him, a gallery is not just about sales – it’s a community, one that cannot be translated online.

While Canada Gallery’s co-founder Grauer said there are benefits to online art shows, he agrees they can never replace in-person experiences, as world-renowned fairs have been career-defining for many gallerists.

“Online art fairs silenced the performance space where art met dealer and dealer met collector,” he said. “It’s all a little too transactional. It just sort of happens like leaves falling or money getting spent.”

Matthew Slotover, co-founder of Frieze, a media and events company that produces the annual Frieze art fair, said physical art fairs will always prevail because of their accessibility. “They are simply the most convenient way to compare such a large body of work in one place,” he said.

People look at work displayed at the Frieze New York art fair in May. Photograph: Justin Lane/EPA

Inside the gallery’s latest exhibition, masked visitors came face-to-face with Mahalchick’s haunting veils of “deplorables”, pausing to inspect each expression. The space was not quite elbow to elbow packed, but the crowded gathering indicates a desire for in-person showrooms. The market was forced to innovate during the past 18 months, but gallery-goers continue to keep what was most crucial at the forefront: the artwork.

And that brings hope to New York City’s gallerists, that this semblance of normalcy is only the beginning of a comeback.

“Usually after a pandemic, there’s always a renaissance,” Gbedemah of Kente Royal Gallery said, referring to the Harlem Renaissance of 1920 that followed the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. “I truly believe that in the next two, three years, there’s going to be an explosion of creativity. We will be able to recoup whatever we lost.”