Source: Art&Object.

Artists, a gallerist, & a historian weigh in on the merits of the style.

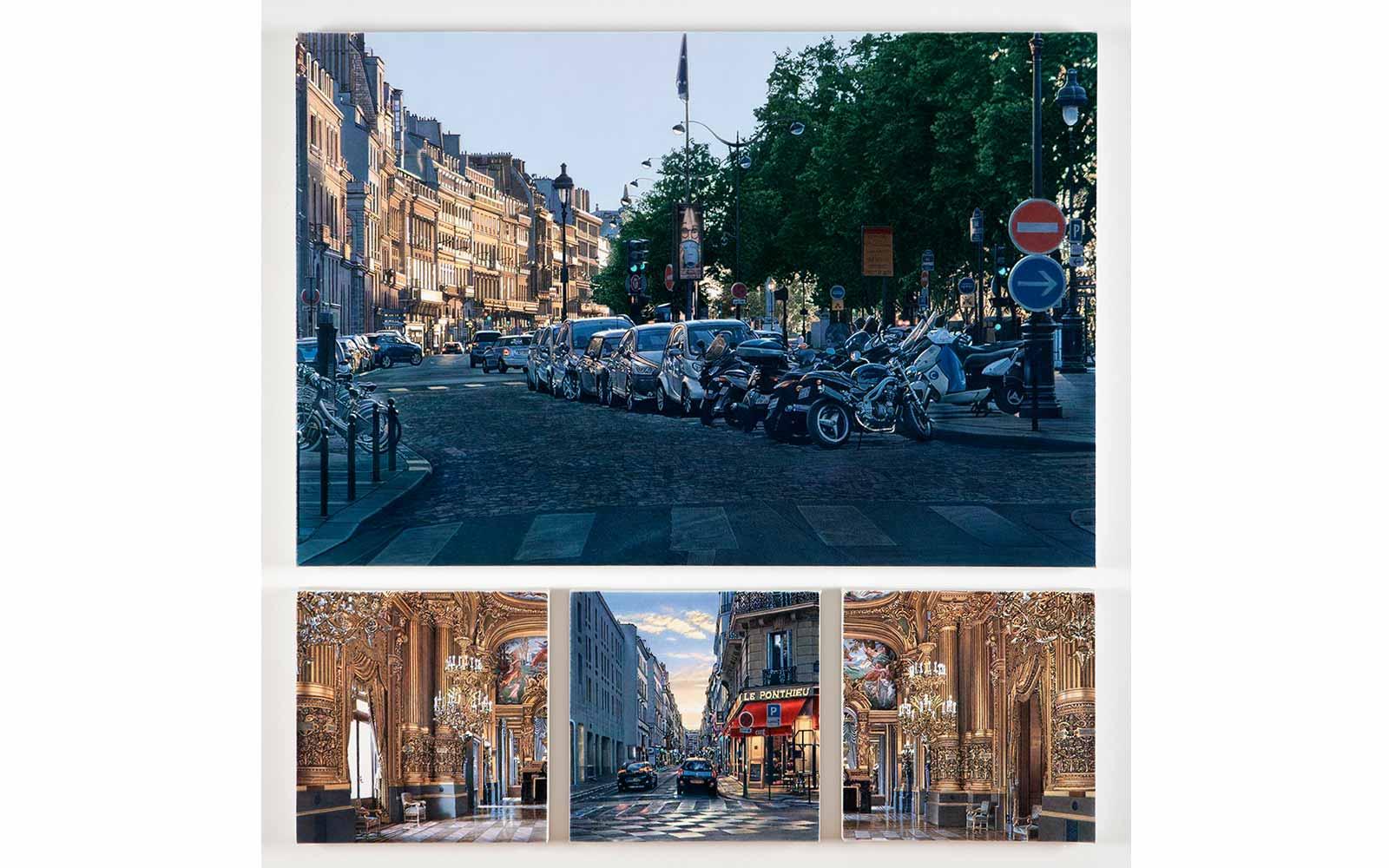

Since the Classical era of Plato and Aristotle, the Greek word mimesis has described the artist’s attempt to reproduce reality. In the twenty-first century, the reality is that Realism continues to matter to the art world.

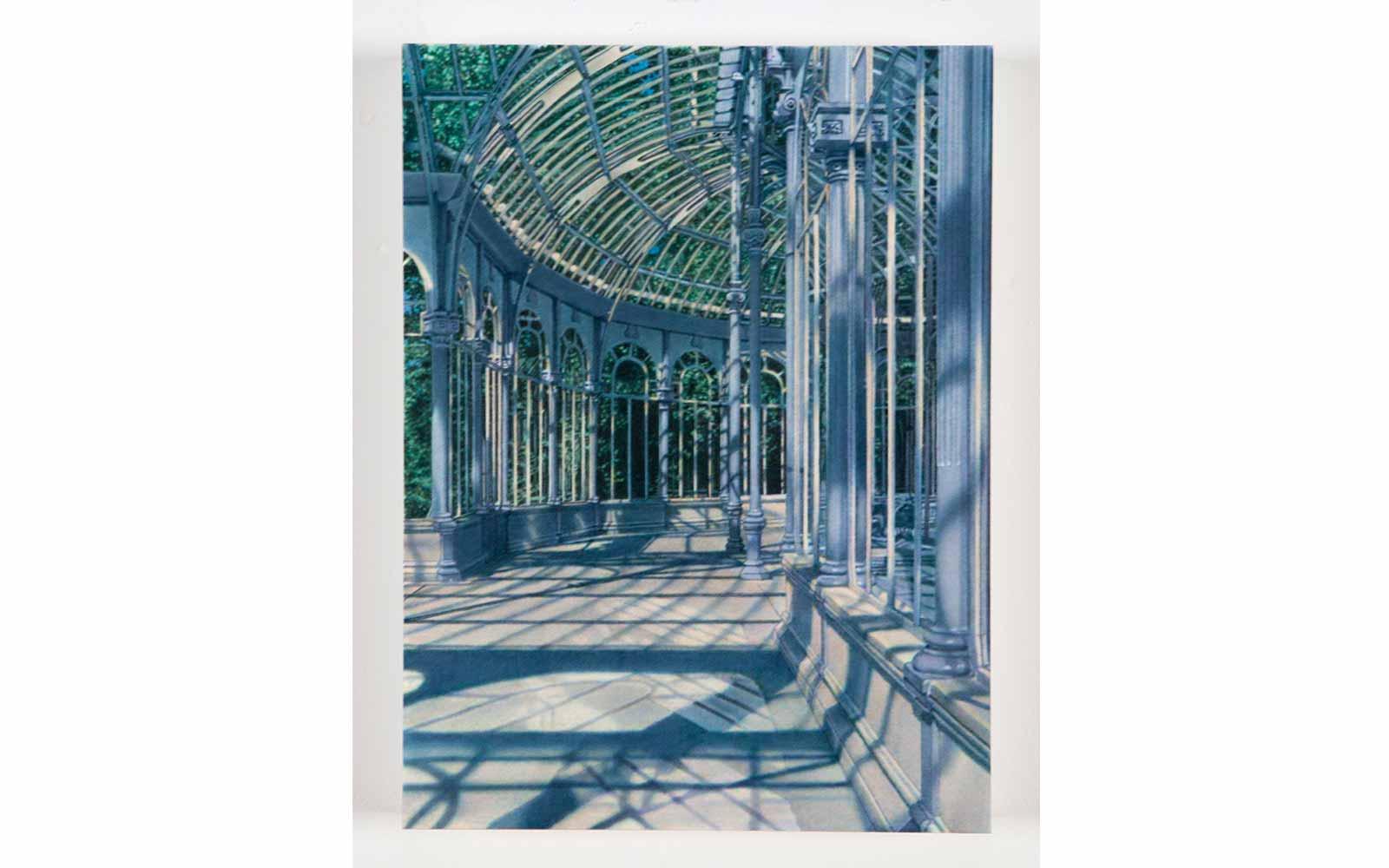

Daniel Sprick, a renowned realist based in Denver, will open his exhibit of interiors on Feb. 11, 2022, at Gerald Peters Gallery in New York City. In a telephone interview, Sprick spoke about the value of representational art.

“If we’re talking about realism in terms of visual representation, the work is accurate and well-crafted based on academic traditions of drawing and skill,” Sprick said. “I love to do it and to look at really good-quality realism works by other artists. realism can be fulfilling and spiritual, a transcendent beauty that is heightened experience.”

Sprick shared an illustrative anecdote about overhearing a snippet of conversation between a couple leaving a museum: “They were walking out of an exhibit of incomprehensible, conceptual stuff, within earshot. The man said to the woman, ‘I know that guy was a genius, but sometimes I want to know it’s good artwork just by looking at it.’ realism is self-evident and needs no explanation.”

Sprick believes realism remains not only relevant, but also flourishing in the twenty-first century.

“There’s no sign of loss of interest among artists with sincerity who want to be challenged,” Sprick said. “I don’t think realism is ever going away. There’s a groundswell of young people finding training outside universities, in ateliers, in private studios, with somebody who has gained academic skill and teaches others.”

Sprick commented on the computer software that transforms photos into facsimiles of oil paintings or watercolors: “They look really good, but are a little too perfect. Even with highly perfectionistic painters like [Johannes] Vermeer, the human hand is evident,” said Sprick. “I can’t get it perfect, and that’s actually a good thing. That makes it more emotionally meaningful to humans. It’s not machine-made.”

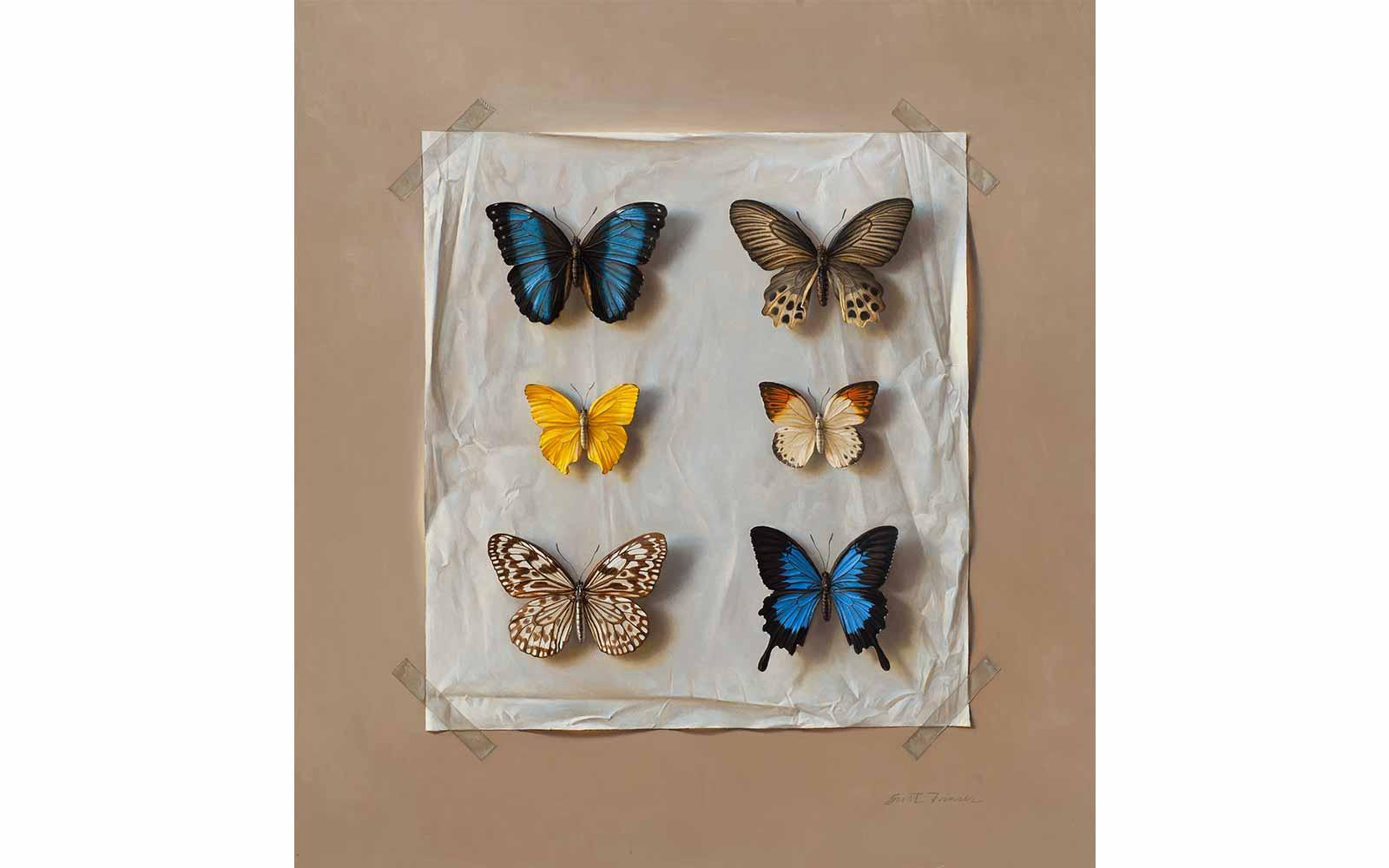

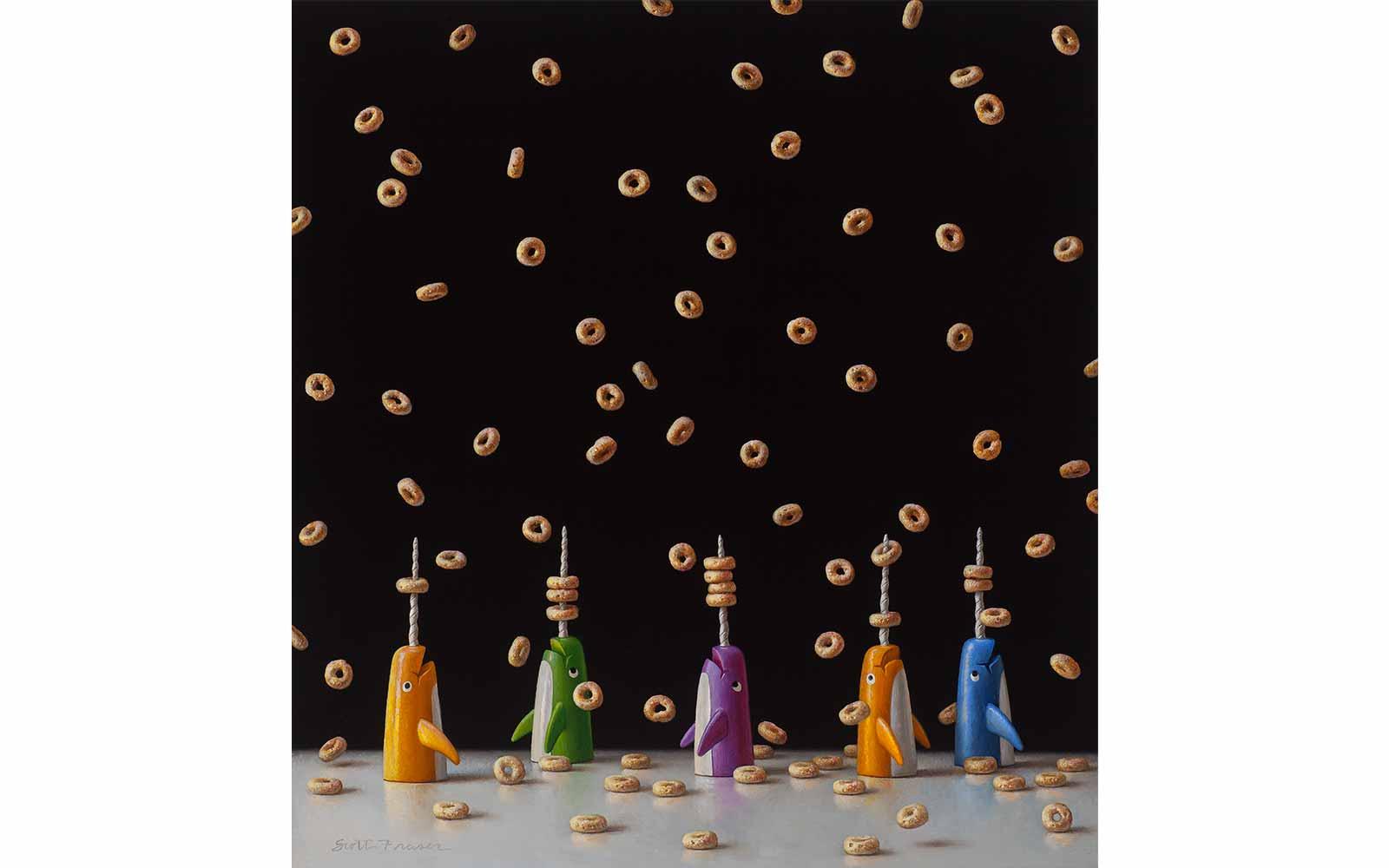

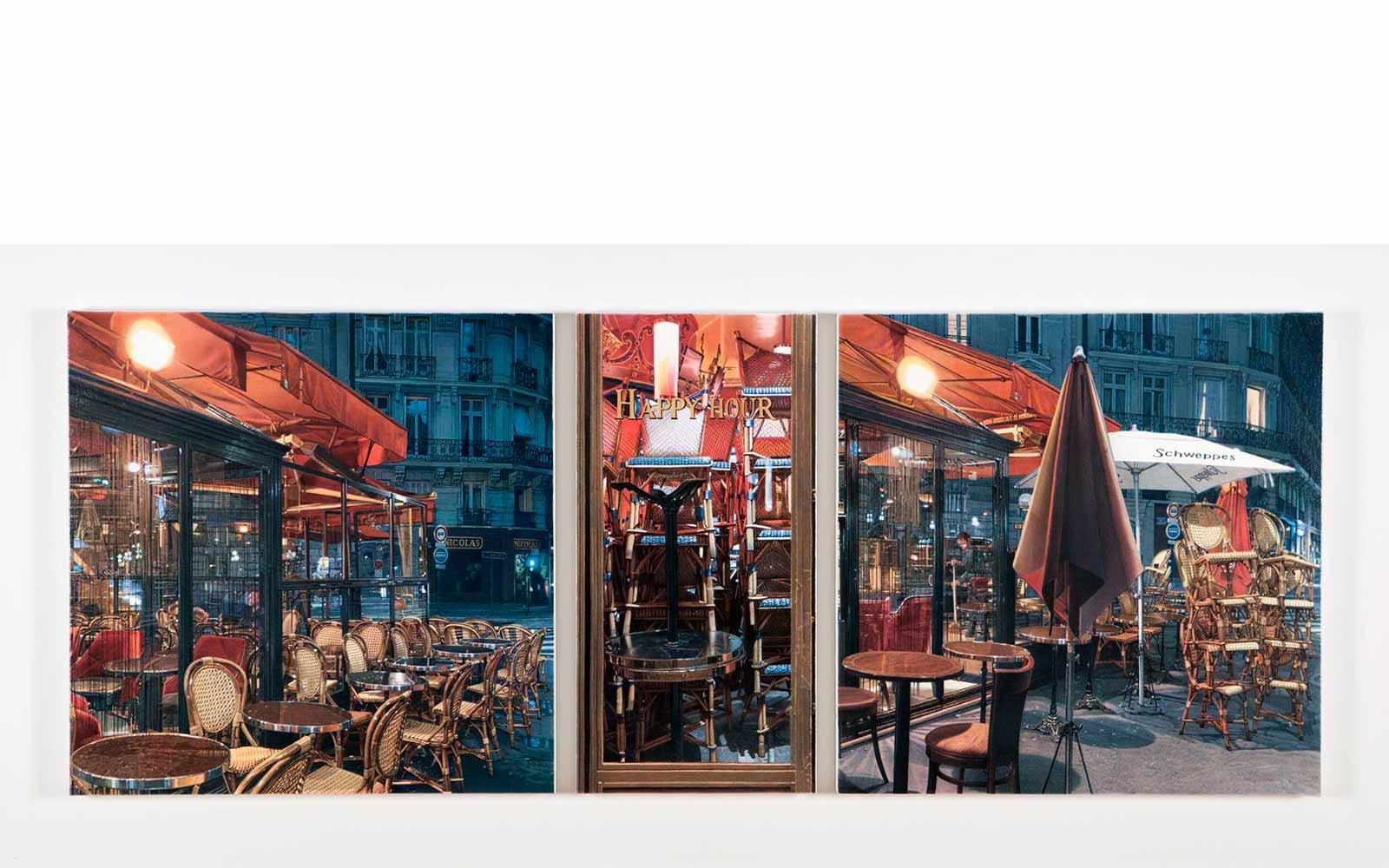

Scott Fraser’s still-life paintings also demonstrate mimesis, but Fraser frequently twists and taunts realism into Surrealism. Fraser’s realism is not bound by reality, but only by his imagination. He emphasized that realism relies upon more than photographic detail.

“It’s not always realism that defines good,” Fraser said. “And there is a lot of cold rendering in realism that I see on Instagram.”

In the twenty-first century, painters can apply unprecedented and constantly evolving technology to realism.

“Some people just trace onto a surface and paint it in. We see a lot of mixed messages today. That’s where we’re at,” Fraser said. “A lot of people can learn to render well, but there’s more: surfaces, texture, color, and the narrative. I go for vision.”

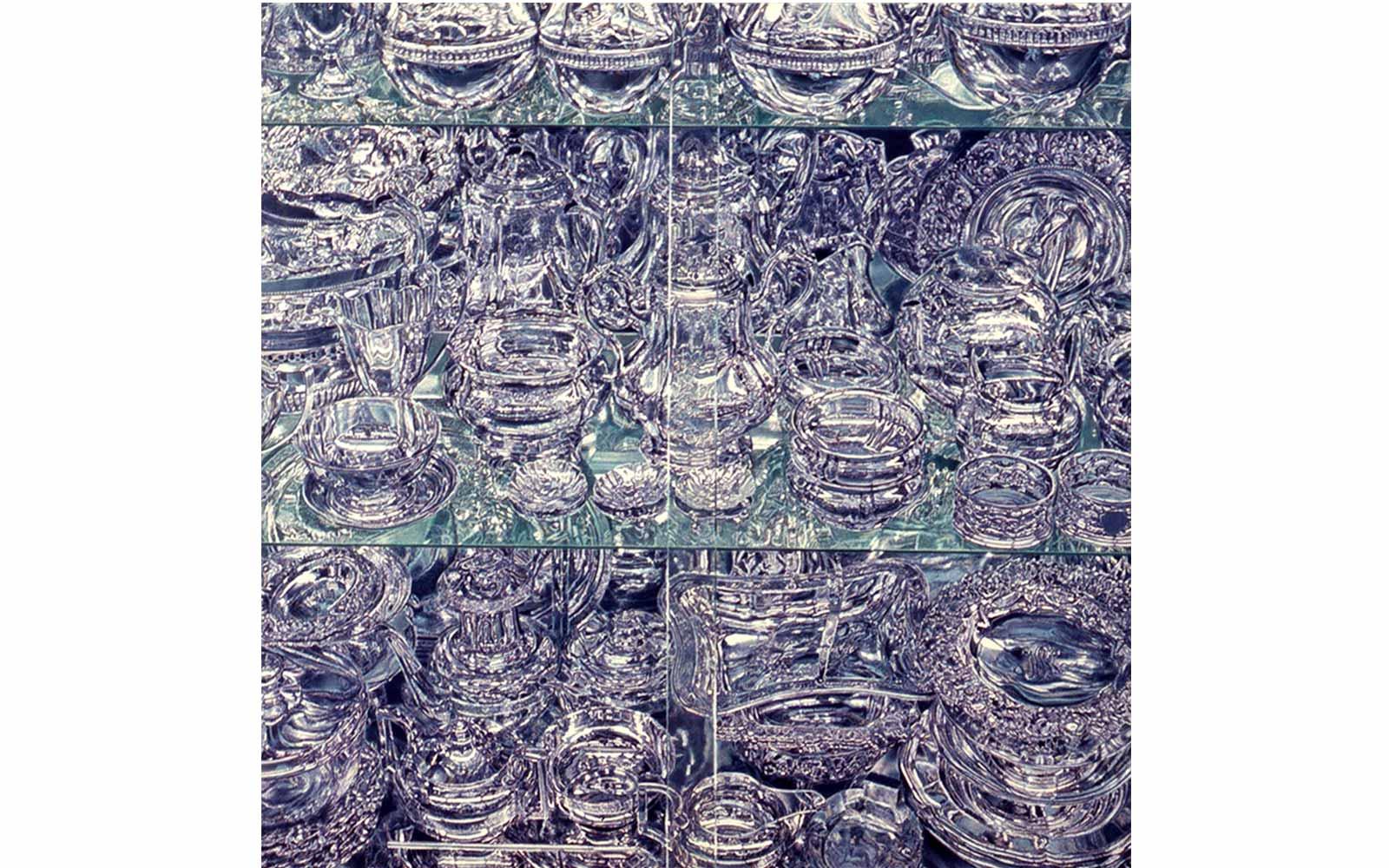

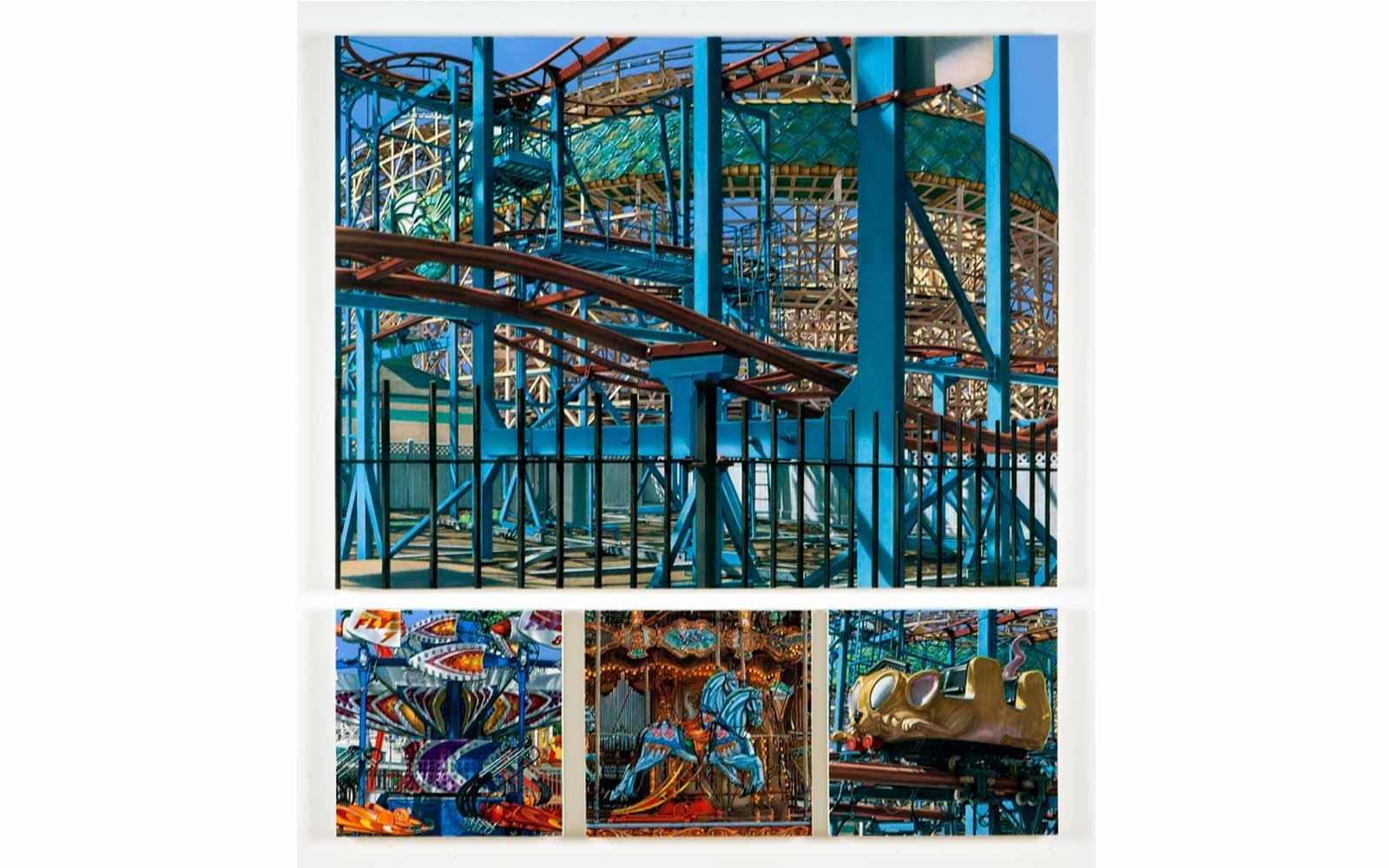

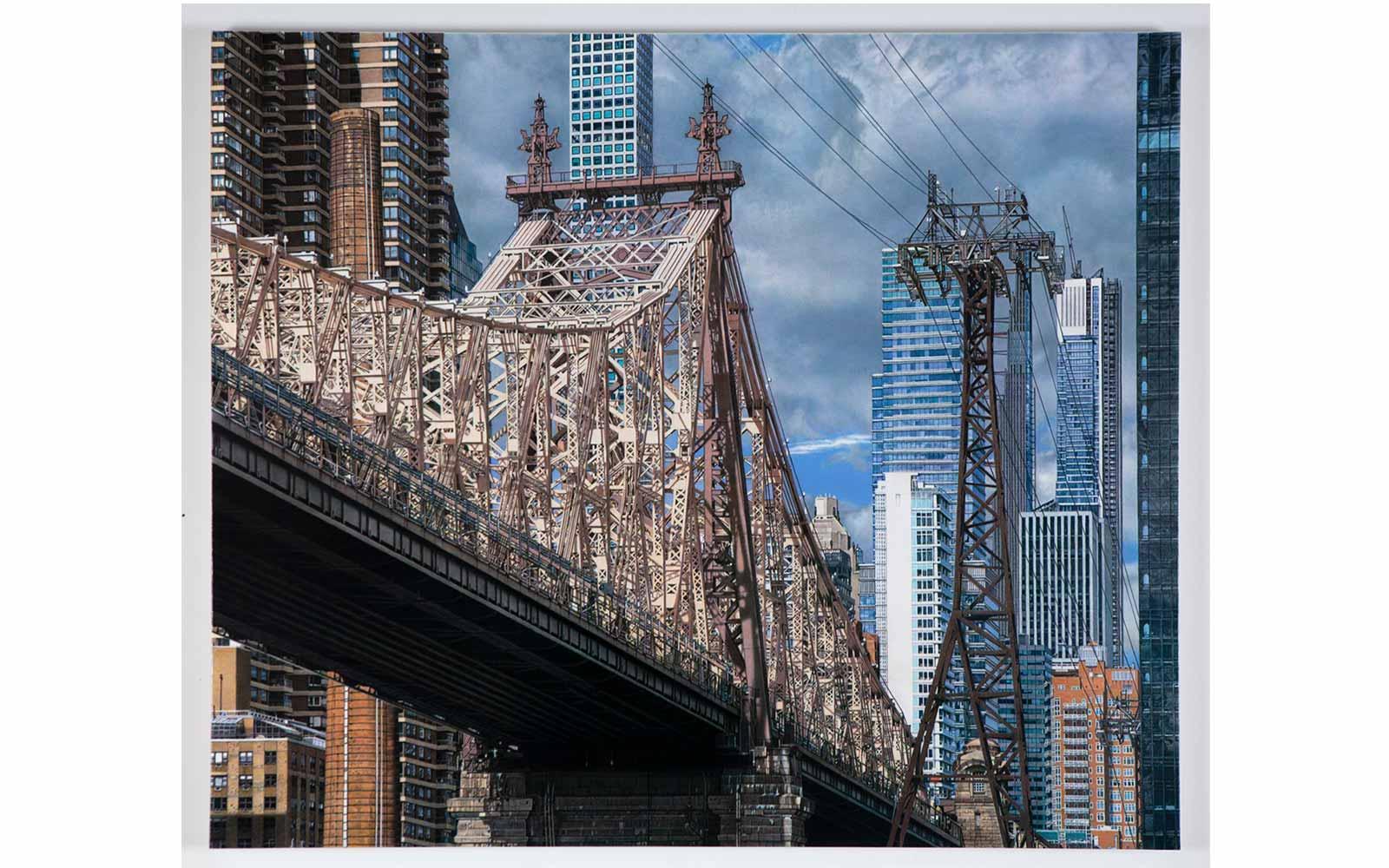

Don Eddy, M. Raphael Silver, 1975.

“Highly representational work with a high degree of verisimilitude is not for everybody. You have to be a certain type.”

Don Eddy

In his artistic process, Fraser remains strictly old-school.

“I work from life exclusively. I don’t even work from photographs,” he said.

Fraser noted the impact of the twenty-first century’s visual distractions and distortions: “There is a lot of competition with images, and people only have so much time,” he said.

“It seems the modern art world is entertainment. Even in museums, people have got to be entertained. That makes it hard for realism because sometimes it’s just a painting on the wall. It’s not being shredded—which for Banksy was clever, but it was more about the publicity stunt than about the painting in the frame before shredding,” Fraser said.

Despite the low points of high-tech, Fraser sees realism as relevant and thriving in today’s world.

“Realism is holding up. More people are able to paint in realism and make a living,” Fraser said. “You look at auctions, and some of the top sales records go to not just Abstract Expressionism. Now realists are selling at auctions, which is nice to see. For a long time they weren’t. The contemporary art market was hotter than the historic art market.”

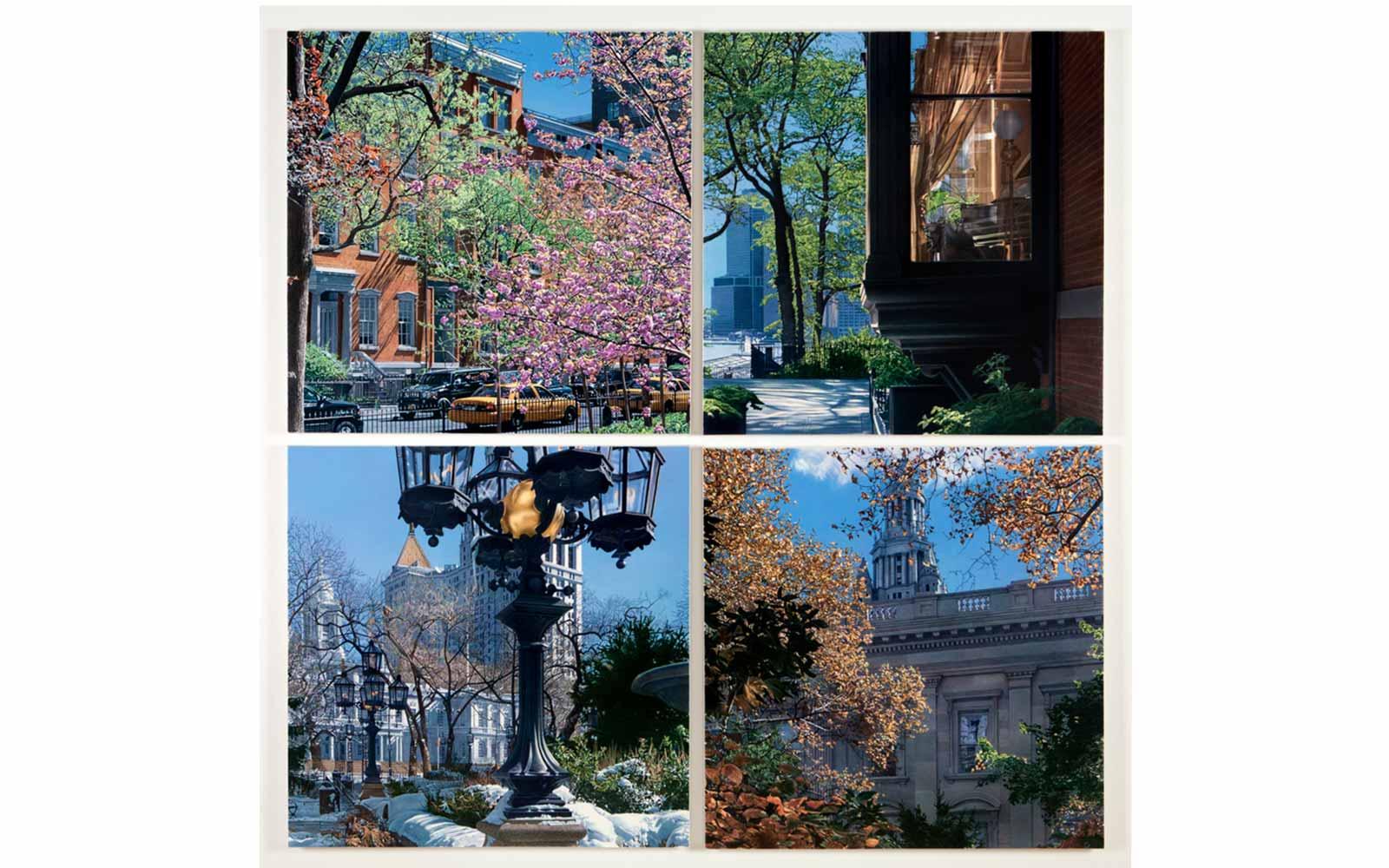

Nancy Hoffman, a New York City gallerist, said in a telephone interview, “No question, there is interest in realism; and like every other movement in art history, the pendulum swings back and forth between Abstract and representational.”

Asked whether collectors she works with demonstrate interest in realist works, Hoffman said, “Definitely. We have a very consistent, loyal clientele interested in representational art.”

Nancy Hoffman Gallery—which opened in SoHo in 1972 and moved to Chelsea in 2008—represents a number of realists, including Don Eddy.

“He was one of the first realists about ideas, not just copying a slide,” Hoffman said. “For the realists, especially of this day and age, execution of vision is intimately tied to their technical ability. I don’t believe it’s about their technical ability. It’s about their vision, but if they weren’t as competent and skilled in the way they express their vision, their work would come across differently.”

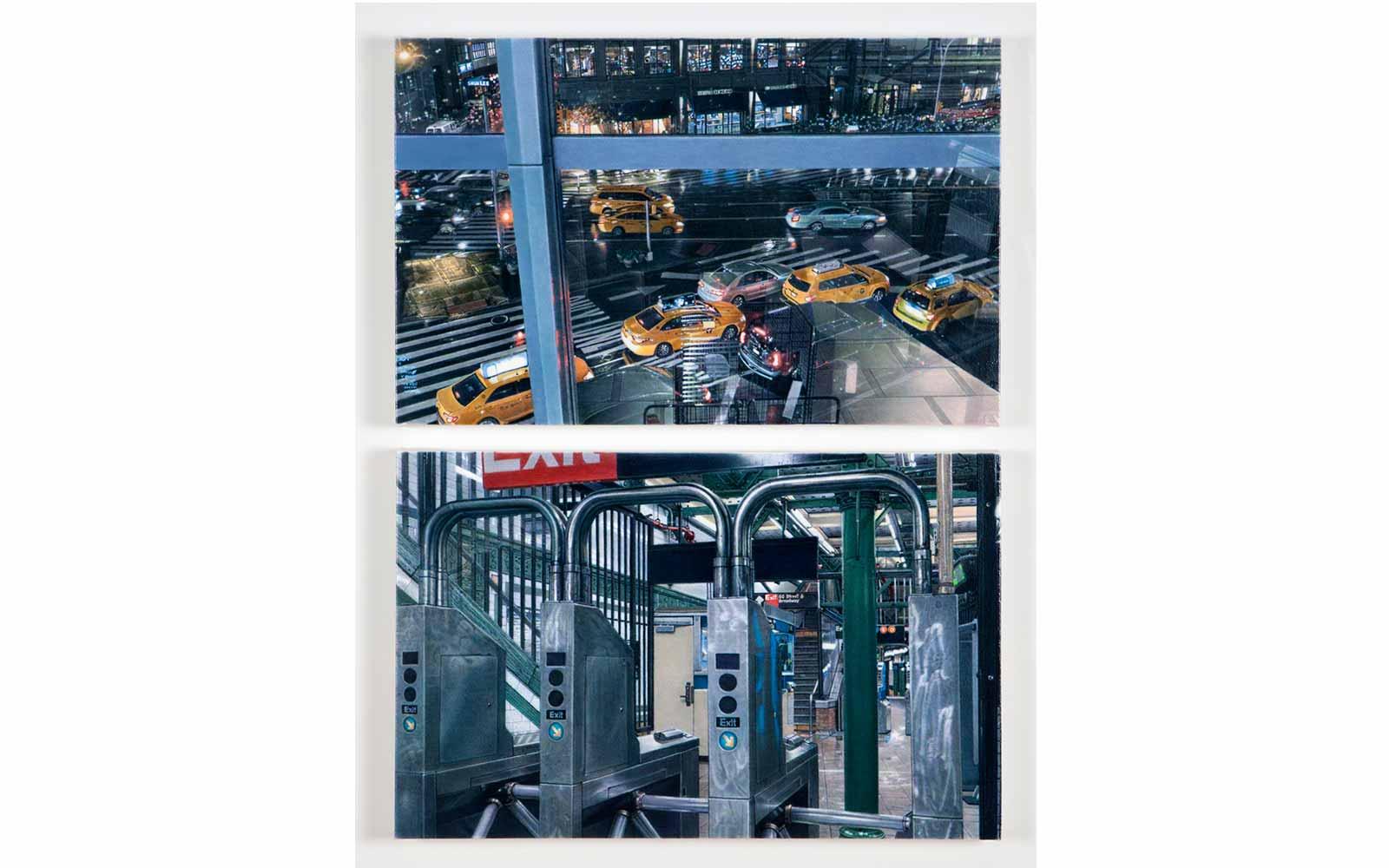

Eddy does not resonate with the word ‘realism.’ He said in a telephone interview, “Philosophically, I have no idea what is real or not. I prefer ‘representational artist.’”

Eddy, too, foresees a bright future for representational art: “My sense through social media, where I am in touch with thousands of paintings from around the world, is that there is a very big and growing movement.”

Eddy uses cameras and computers in his artistic process, detailed at this link.

“Technology is very useful to me,” said Eddy, whose paintings approach such mimesis as to cause an onlooker to wonder whether the works are photographic.

“Highly representational work with a high degree of verisimilitude is not for everybody. You have to be a certain type,” Eddy said. “For most people, it’s beyond what they have patience for, but there are those who have to give voice to an obsessive-compulsive nature. It goes beyond patience to madness.”

Henry Adams, Professor of Art History at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH, sees realism as vital even—or especially—in the age of virtual reality, artificial intelligence, and as of yet unforeseen technology.

“One of the interesting developments of the twentieth century is that due to digital imagery, imagery has become as much a part of daily communication as words,” Adams wrote in an email interview.

Adams suggested that political strife inspired a return to realism. “Cutting-edge artists have come to feel that ‘abstraction’ is not the best way to deal with some of the most immediately pressing concerns of human existence such as gender, race, social injustice, human relationships and conflicts, or man’s relationship to nature.”

Human nature—at least for now—continues to value the aesthetic of mimesis in a world where it has become increasingly difficult to separate what is real and what is not.