Source: Medium.

Can you derive pleasure from viewing art through a screen, the same way you would viewing art placed physically before you?

Famous last words:

“I can enjoy the artwork from Google, at the click of a button. No need to go to a museum or gallery.”

“Everything is digitised anyway.”

The Proliferation of Galleries and Museums

Photo by Vladimir Ivanov on Unsplash

There is something mesmerising to stand before one of the great masterpieces or a controversial block of white paint, breathing in the same air as a piece of unique history and technique that has existed for decades or centuries prior to your own birth.

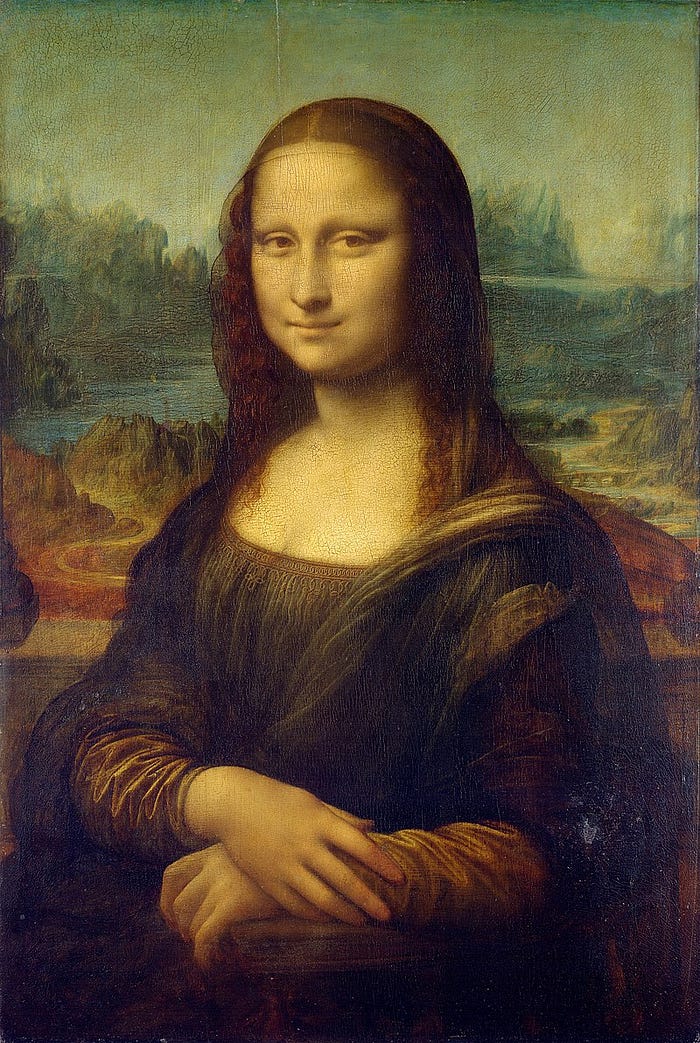

Yet, with the proliferation of technology, and more importantly, the appreciation and reliance on technological advancements to distribute, present, and even curate art, anyone with access to a computing device and the know-how, can easily access and appreciate Edouard Manet’s Olympia, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, or even Vincent Namatjira’s Queen Elizabeth And Vincent (On Country) from the comfort of their couch.

Edouard Manet, Olympia, Oil on canvas, 130 x 190 cm, 1832–1883. Photo credits: https://m.musee-orsay.fr/en/works/commentaire_id/zoom/olympia-7087.html

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, Oil on poplar panel, 77 x 53cm, c. . 1503–1506, perhaps continuing until c. 1517. Photo credits: https://focus.louvre.fr/en/mona-lisa

Vincent Namatjira, Queen Elizabeth And Vincent (On Country), acrylic on canvas, 48 ? 61″, 2018. Photo credits: https://www.artforum.com/print/201908/wes-hill-on-vincent-namatjira-s-queen-elizabeth-and-vincent-on-country-2018-80815

Software has even allowed really anyone to zoom in and out of a substantial amount of artwork, enabling the viewer with a better look at the textures, brush strokes, colour, and deterioration over time — of say Mona Lisa — than one would visiting it at the Louvre.

Artistic Impressions

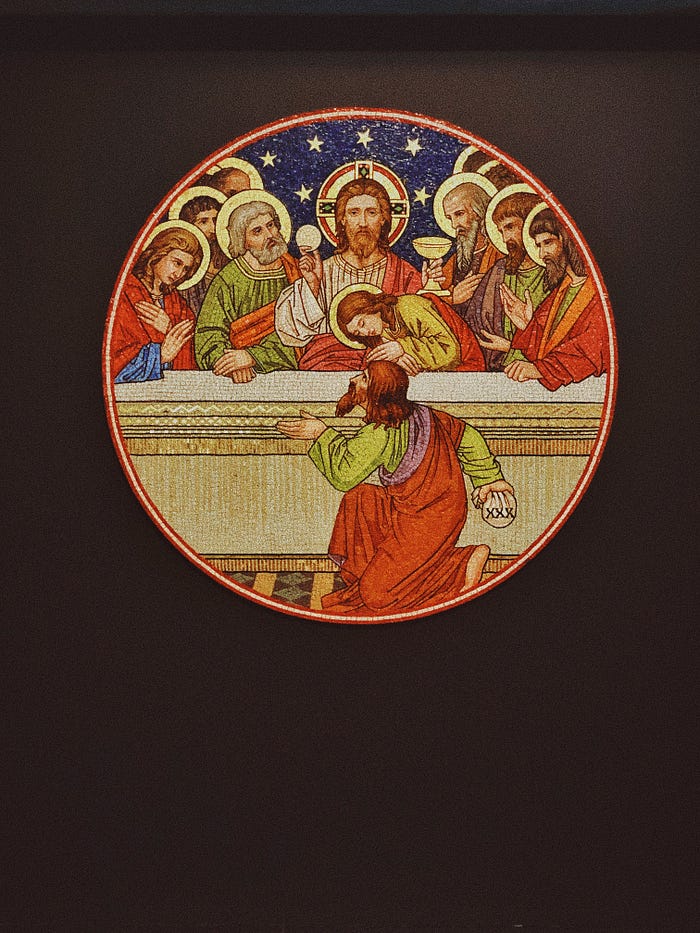

Photo credits: @yesnodunno. Salviati & Co., The Last Supper Panel, glass, lead, iron, mortar, 118.7 X118.7 X 1.3 cm, c. 1880.

The ideal impression a work of art makes in inherently tied to the engagement between artwork and viewer; the experience it invokes in the viewer who gazes upon it, as Hagman attests to:

Art appreciation is enhanced when one engages the artwork, attending to one’s critical attitudes as well as one’s sense of resonance and conjunction. The art appreciator “meets’’ the artwork. There ensues a process of implicit, preconscious procedural knowing in which the formal, visceral and representative aspects of the work, which are the concretised subjectivity of the creator, impact on the viewer eliciting a response on multiple levels. Archaic, self and other experiences are activated during the encounter with the art object. In the best of cases this experience of meeting is intensely affective and profoundly moving — a perfect experience. In the language of first relationships, the good feed becomes the ideal feed in which all is idealised and made well again.

— George Hagman, “A New Psychoanalytic Model of Aesthetics”, The Artist’s Mind : A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Creativity, Taylor and Francis, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 15.

Arguably, the impression a work of art imposes on its viewer cannot be replicated through digital technology. There is no software presently available that would accurately replicate the sensory complexities one would experience in the physical presence of a Venice manufactured panel or woven tapestry. While the visual experience of achieved through a high resolution screen is no match for the naked eye, but other elements tied to the artwork’s very essence and impression, like the musty odour given off – a significant element of the work’s historical or geological presence all make up the viewing experience.

Interaction As Art

Photo credits: @yesnodunno, Yayoi Kusama, Flower Obsession, flower decals, fabric flowers, furniture, found objects, 330.0 ? 1890.0 ? 1480.0 cm (variable) (installation), 2017.

Yet there are still several large concerns and limitations that the technological advancement of the art through a screen phenomenon cannot relinquish.

Take installation or interactive pieces for example, where the audience becomes an inherent a part of the artwork. Yayoi Kusama’s Flower Obsession in particular would cease to exist without the gallery visitor’s contribution to it; visitors are presented with a flower decal or sticker that they would be permitted, and even encouraged to apply on any of the furnishings within the exhibition space.

Over time, a once bare, seemingly unappealing white cube with several couches and shelves littered across an approximate 2 bed-room space soon transforms with the flourishing application of flower decals affixed by visitors, enabling a masterfully curated space well worthy of instagram photos.

I have no doubt that with technological softwares, savvy guests could as easily apply a flower decal virtually through the click of a button, on any — if not the less achievable positions like on the ceiling, that one would struggle to physically due to physical limitations—composing an equally unique Flower Obsession that would be accessible online.

Although somehow, many have managed to achieve so out of sheer will, dedication, or perhaps with astonishing physical prowess:

Photo credits: Eugene Hyland, from https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2018/04/yayoi-kusamas-flower-obsession/

Yet, it would ironically detract from the very purpose of the exhibit: the realisation of obliterating a physical, domestic space with thousands of ready-made art work. Achieving this spectacle virtually would be akin to a sort of sensory deprivation for the viewer — the overwhelming sensory activation achieved through physically experiencing a sort of visual hallucination would simply not be possible to be transferred through a two dimensional image on a screen.

Although if you do find yourself experiencing any form of vertigo when viewing Flower Obsession on your computer screen, you might want to pay a visit to your doctor (this is not a joke).

Appreciating Art In The Digital Age: Art Living In The Mind As Much As It Does In The Eye

Despite all my grievances with the current state of the Arts X Tech movement; the overachieving idealism that academics or audiences have attributed to a still tenuous relationship, it is imperative to take a step back and appreciate the advancements made for Art history, curatorship, and creation in the digital age.

Take the proliferation of the controversial NFT, the talented Refik Anadol’s audio-visual performance Machine Hallucination, or even the often overlooked collection management software employed in museums or galleries for instance, the digital age has undoubtedly made its mark in the art world.

Photo credits: https://refikanadol.com/works/machine-hallucination/

The Arts X Tech phenomenon is no longer merely

. . . but the latest in a string of interpretive and imaging technologies devised to copy, distribute and presence collections.

Haidy Geismar, Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age, pp. 106

It can and will offer so much more when utilised effectively and innovatively.

“I saw the entire room, my entire body, and the entire universe covered with red flowers, and in that instant my soul was obliterated … This was not an illusion but reality itself.”

— Yayoi Kusama, on Flower Obsession for the NGV Triennial 2017

Photo credits: https://www.todayonline.com/entertainment/japanese-artist-yayoi-kusamas-brings-hope-through-art

Ironically,

Much like we view an image on our computing screens — a product of pixels densely compacted onto a 23 inch monitor or palm sized phone — Kusama invites us to view her world through a similarly, and categorically parallel “screen” that is her art.

Call it a reflection, and image imposed, pointilism rejuvenated, or information congealed and packaged for consumption, at the end of the day, the image of Kusama’s Flower Obsession or Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker reflected to us through a digital medium is nonetheless a presentation of artistic information, albeit of a different kind.

If an image of an image is artistically pleasurable to you and real enough for you, then who’s to say that that poorly photocopied (copyright laws!!!) image of Mona Lisa hanging in over your kitchen sink exudes no artistic reality? After all, art exists not just in the flesh, in our eye, but also in our minds. Ponder.