Source: ARTNews.

Marion Maneker of ARTNews reflects on art as an asset and reasonably wonders after two decades of dramatically rising art prices whether art has not finally become an asset class, as some have hoped and many others feared.

“People have long used art to store value,” Miami-based NFT investor Robert Rodriguez-Frail told Business Insider after he sold a Beeple NFT for a lot of money in March. “Crypto extends easily into digital art. This is just a more modern approach to investing in art and using it like someone would use gold or bitcoin.”

Rodriguez-Frail had originally bought his Beeple five months earlier for $67,000; he sold it for $6.6 million. That kind of 100-fold return isn’t really evidence of art being a “store of value.” Yet one of the underacknowledged factors contributing to the rise of this year’s NFT-mania is an overall assumption built up over the last two decades of the rise in art values that art is an asset class.

There is no doubt that some art has become extremely valuable—for certain collectors, holdings of art have become their most valuable asset. Linda and Harry Macklowe await the disbursal of their collection estimated to be worth more than $700 million. When the estate of Sally and Victor Ganz was sold 25 years ago, the value of their art dwarfed their other holdings. Even David Rockefeller, whose collection sold for more than $835 million in 2018, wrote in his Memoirs, “While we never bought paintings as an investment, our art collection has become one of my most valuable assets and represents a significant part of my personal wealth.”

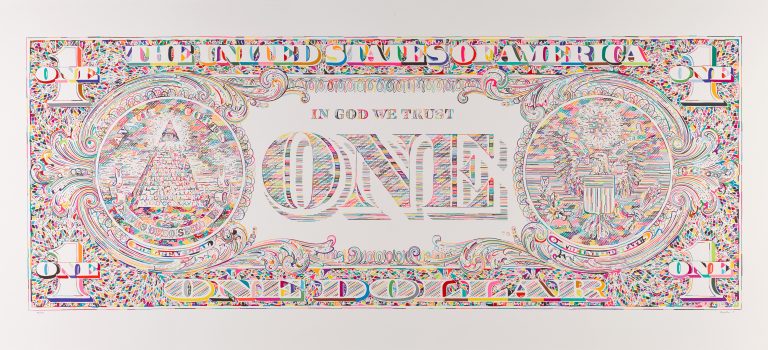

Because high-quality art has also become high-value art (in many, though hardly all, cases), there has been a tendency to view all art as valuable and something to be treated as an asset. An asset is simply something that you know someone will buy from you sometime in the future. If you are reasonably confident in the price someone will pay in the future, you can use that asset in a number of different financial ways. But once art becomes an asset, many detractors fear, it ceases to be seen as art. To put it another way, when you look at a work of art that has become an asset, you have a hard time seeing the art itself—its beauty, its formal innovations, its cultural or social ideas. Instead, you just see the price someone is likely to pay for it. Wondering whether it will increase or decrease in value, you worry about its future price more than you enjoy the art itself.

Think of it this way: When collectors buy works of art as an asset, they’re buying them the way most people buy a house. The hope that your home will increase in value isn’t the only reason to buy a house. But when faced with a major financial purchase, most people don’t want to imagine that they will lose money or, worse, that their house might one day become worthless.

Financial assets are created to serve financial ends. Art is not. Gerhard Richter’s paintings are among the most valuable artworks in the world, but he didn’t make them for that purpose. Richter paints to explore the ideas he has about art and aesthetics. Each new painting is a chance to work out those ideas until he feels he’s fully explored them or otherwise abandons them. We can say the same for almost every artist, which raises the obvious question: why does anybody buy art as an investment?

For ordinary folks, cash is scarce. If they want things they cannot afford, they can take out a loan to buy a car or a house or even luxuries like a boat. These folks pay a premium for that privilege. The rich have an entirely different problem: too much cash and too few places to put it.

Over the past two decades and especially in the last few years, the wealthy have gotten a lot wealthier. Beginning around the turn of the century, in response to the dot-com bust and the 9/11 terror attacks, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve lowered interest rates and then began a broader program of injecting cash or liquidity into the global financial system. Low interest rates and easy cash have two effects on the world’s economy: The first is that it makes unattractive the kinds of safe investments that savers use to store the value of their household prudence. Everything from U.S. Treasury notes to bank CDs to many types of bonds provide little return for investors, which leaves savers searching for returns by unconventional means. A second effect of all that liquidity is that the wealthy have a great deal more purchasing power. These days, if you own a business or have some other sort of substantial and reliable income, you can borrow money for next to nothing.

The result has been two decades of very easy money—and a newly created global population of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals, as the private banking people like to call them, with $30 million in liquid assets (which means money beyond the value of their primary residence). Knight Frank’s 2021 Wealth Report estimated that there were 521,000 UHNWI in the world in 2020. Fewer than a third of those, 190,000, lived in the United States, 151,000 lived in Europe and 116,000 more in China.

Even before the world was so awash in cash, art attracted money. For many, the heady combination of direct or indirect connection to a great person from the past has made art even more valuable than money. Whether a piece of porcelain formerly owned by an emperor, one of Leonardo’s notebooks handed down from a plutocrat, or a sublime painting from a pivotal moment in an artist’s oeuvre, the owner of an artwork can be reasonably confident there will be a next person to come along and be willing to pay (one hopes) more for it. In that sense, art is a different kind of asset whose appeal is steady and lasting. Central banks may flood the economy with currency, but there will always be a demand for art, the thinking goes.

Money began to flow in earnest into the art market in 2004, rising sharply in 2007, and peaking in 2008 before the credit crisis brought everything to a halt. Sooner than most expected, the market began to stir again early in 2009 when the wealthiest showed a willingness to spend money on art in ways that shocked many. From 2010 to 2015, the art market rose and rose again, posting remarkable prices that created the popular impression that art was a buoyant asset immune to the pressures of normal economics.

The prospect of making a killing by buying and selling art is hardly new. In 1904 André Level got the idea to start an art fund he called La Peau de l’Ours, or Skin of the Bear, through which he was able to buy 100 works by artists like Chagall, Picasso, and van Gogh. Ten years later, they sold off the paintings for quadruple their investment.

Given those strong results, it’s surprising that it took another 60 years before someone tried it again at scale. In 1974 the British Railroad Pension Fund struck a deal with Sotheby’s to spend £40 million ($70 million) to acquire 2,400 artworks that it would hold as a hedge against inflation. Over the next few decades, the art was sold at a profit—much of it concentrated in a group of Impressionist paintings that had become quite valuable in the 1980s art boom.

Sensing an opportunity, several firms tried to exploit it by creating funds meant to offer investors passive exposure to the value of art by accumulating substantial and diverse holdings. The only problem with that strategy has been the size of the art market. No one really knows the market’s true size because so much of its activity transpires in private transactions. Clare McAndrew, the economist who provides the most consistent and authoritative art market numbers in her yearly Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, puts the market’s activity in the range of $57 to $68 billion over the last decade.

BlackRock, one of the world’s largest managers of other people’s money, has nearly $8 trillion under management, according to its 2020 figures. Private banks and other institutions have trillions more that they invest for their clients. If just BlackRock were to decide to devote 3 percent of its clients’ money to art, that would mean having $240 billion invested in the art world. If just 10 percent of that art were sold in any given year, it would account for more than a third of the entire annual turnover of the art market, creating a level of volatility in prices that would undermine the whole concept of art as an asset that does not correlate to other markets.

In the meantime, private banks figured out an easier way to make money from their clients’ art collections. Sophisticated financial players including Michael Steinhardt, a legend among early hedge-fund investors, learned they could use their collections as collateral against large loans and lower their interest rates even further than the low existing rates. The banks still made money but with far less hassle than trying to buy, manage, and liquidate art themselves.

That the financial industry settled on lending might appear to validate the idea that art is indeed an asset. But it turns out those art loans are not quite what they seem. Lenders who have tried to use art as an unsecured asset have struggled. It’s the private banks, with recourse to more than just their clients’ art assets if a loan goes bad, that have succeeded and dominated the art lending business. For all the supposed value of blue-chip art, no one in finance has really figured out how to fall back on art as an asset.

These are smart people, so there must be a reason. Part of the problem is that today’s blue-chip art could be tomorrow’s obscurity. The Old Masters market, which once dominated value in the late 19th and 20th centuries, went through a painful transition in the 1970s when tastes changed. Likewise, the market for antique furniture has experienced a fall from grace over the last two decades. The Impressionist market is beginning to show signs of evaporating demand around the edges, signaled at first by lower prices for minor artists as well as lesser works by the major names.

Going against the fears of those who claim that art buyers care only about price, the current market is dominated by Black figurative painters, women artists in different genres, and Asian artists. The record prices being paid for work of increasing diversity are a reflection of not just rising wealth in the world. And they do not owe solely to the expectation that the artworks will retain their value. A buyer may hope for that, but no newly escalated price is paid without high risk. Everyone knows this—it’s part of the thrill.

This idea that art is chiefly about prices also misses something even more important. Artists represented by international galleries whose works might be traded at auction are a small, select group. The bulk of artists and artisans show their work in a wide variety of venues far beyond the galleries in global hubs. Artists interact with followers and collectors directly on Instagram and through dozens of websites. Others, as we saw with such poignancy last summer, are decorating walls and streets to express their outrage over injustices like the murder of George Floyd. These artists do not consider the price of their work when they paint a memorial.