Source: Artland.

National galleries exist to serve their audience with the most quality and educational showings of historical works and subjects as well as the current state of their nations’ artistic scene. As publicly funded institutions, providing visitors with appropriate and societally meaningful discourse surrounding their works should be the cornerstones of their missions. But does serving the public with the most popularly regarded, biggest name shows fulfill this goal?

Today, colossuses in the development of modern visual art still stand out as a tourist draw across the globe. However, if some of these favorite artists were alive today, with public knowledge of their lifestyles and dangerous viewpoints of the world – which were accepted at their time and often even contributed to their success – would they still have a spot at these institutions and beloved status from the public?

There’s also no argument that these historical figures made countless innovations to their field during their times, no doubt about their technical skill and the importance of these works in western art history. But it would be impossible and outright irresponsible to separate the art from the artist. So if we are to take the stance that there is still value in showing these works to the public, then what is the best way to do so? And what should be the role of the highest art intuitions? Through several recent examples, we take a deeper look and question the role of Western national galleries in conveying the proper story behind the art to their audiences.

Paul Gauguin, Tehamana Has Many Parents or The Ancestors of Tehamana (Merahi metua no Tehamana), 1893. Oil on coarse fabric, 75 × 53 cm. Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Deering McCormick (1980.613). Photo: Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Recent Interpretations of Gauguin

The most famous example of a classic art world favorite but subject to recent questioning of ethics is the French impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, beloved for decades and hailed for his revolution in expression. Many admirers still cling to praising his representations and portraiture of Polynesian women and young girls despite the revealed sexualized lens, and his capturing of Tahiti and other islands of French Polynesia as a tropical paradise during his time in the French colonial possession. However, it’s now widely known that Gauguin’s time in the tropics was anything but paradise as he left behind his Danish wife and family in France, “married” a 14-year-old Tahitian girl and engaged in abusive sexual relations with several women and young girls who were the subjects of his famous portraits.

From late 2019 to early 2020, an exhibition traveling between major public institutions including the National Gallery of Canada in Ottowa and The National Gallery in London displayed some of the largest single showings of Gauguin’s works in recent times, providing a recontextualization of the infamous painter.

In the first iteration of the show at the National Gallery of Canada, the interpretation efforts surrounding the show were in the eyes of some seen as insufficient or even apologetic towards these issues. Wall text lightly addressed the problems with words such as ‘savage’ or ‘barbarian’ used to describe the people of Tahiti, written off as products of the time: “considered offensive today, reflect attitudes common to Gauguin’s time and place.” But even with some press pushback towards the show, the public feedback was comparatively subdued with only 50 out of 2,313 comment cards expressing discontent over the Gauguin programming. The London reiteration of the show did admittedly take this contextualization further, even asking audiences if it was time to stop looking at Gauguin altogether in their audio guides.

Contes Barbares (Barbarian Tales) 1902 Oil on canvas, 130 x 89 cm Museum Folkwang, Essen

Following these events – and even with the National Gallery of Canada’s director admitting the museum’s shortcomings in contextualizing the show – a current lookup of related material on each of the institutions’ websites largely erases the contextualization efforts made to reveal these aspects of the artist’s life. At most, they shortly brush upon his privilege as a European man during his times. Yet, the overall tone praises his style innovation and approach to naturalism, with no mention of the relations with the 13-14-year-old girl.

Conversely, in 2020 the Tate Modern in London unveiled Fons Americanus, a work by American artist Kara Walker, which confronted the Anglo world’s own colonial past. The work was received with a huge response and was even featured in FKA Twigs’ video for Don’t Judge Me. Shown at an institution focused on contemporary expression such as the Tate Modern, Fons Americanus resounded with a group that was aware of the issues the work was seeking to address – showing that audiences, depending on the context, are more ready to handle this subject matter. So does the problem rather lie within the public or the institutions? And is it even too late to shed light on untold narratives?

Emil Nolde, Tänzerin, 1913. Städel Museum © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll.

How Much Interpretation is Enough?

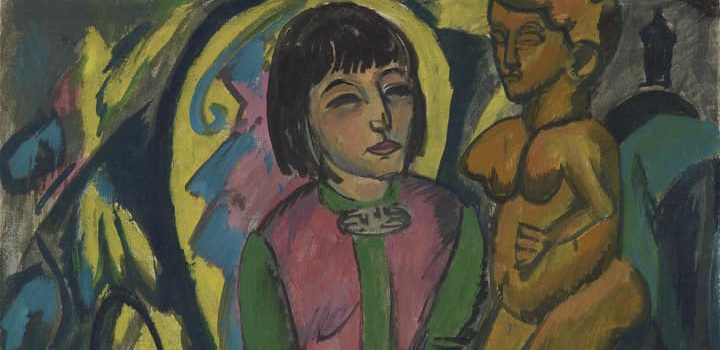

In their major spring 2021 presentation, the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) made room in their re-opening line-up for a particularly special exhibition: Kirchner and Nolde up for discussion, to then be shown at national institutions in both Germany and the Netherlands. Known for its extensive classical collection of royal possessions and acquisitions, SMK re-examined the work of two German “anthropological” artists through curatorial decisions and textual material brought in contextual information not only regarding the two artists themselves, but also the surrounding colonial horrors taking place at the time. The works were accompanied by material covering topics such as appropriation, the European attitude towards race at the time, and the overall spectacle of other cultures by European audiences. Audiences were furthermore confronted with authentic artworks from Oceania and Africa, side by side with copies created by the two German artists, those works that gave them their famed status.

An exhibition with this level of self-examination and context in interpretation is almost unprecedented from a Northern European classical institution. In fact, while a country like Denmark is often praised for its societal advances and overall happiness factor, many often overlook the effects of its colonial history. This, however, is not the case: the museum boasts an extensive collection of ultra-contemporary Danish artists across a suspended catwalk connecting the classic building to the newer build modern structure, where a handful of works confront the current racial struggles and colonial power structures within the country today. Works like that by Danish-Philippine artist Lilibeth Cuenca Rassmussen attack the issue much more head-on where the meaning can be taken without the need of wall text explanations.

It’s perhaps time to question if high-attendance sell-out shows alone are the true measure of success for national institutions. When taking into consideration the average museum-goer, how many are avid readers of the text provided to them by the museum? No matter how comprehensive it may be, there will always be a large portion of the audience merely driven by the visuals, a portion interacting on the surface level with works, in search of the perfect Instagram backdrop. Tackling these issues head-on may require much less subtlety than previously thought.