Source: Artsy.

The statistics of the past few decades confirm that the art world is not one of gender parity. Works by female artists comprise a small share of major permanent collections in the U.S. and Europe, while at auction, women’s artworks sell for a significant discount compared with men’s. Sociologist Taylor Whitten Brown explores the reasons of this inequality.

Only two works by women have ever broken into the top 100 auction sales for paintings, despite women being the subject matter for approximately half of the top 25.

It is not hard to grasp the origins of this inequality, given that women were largely barred from artistic professions and training until the 1870s. Untangling the reasons that this inequality persists today is more difficult. Differences in gallery representation; the cultural biases of art interpretation; the cliché of the art world “bad boy”; the sexism of aging; the imbalanced weight of parenthood; the proportion of curators, collectors, and gallery representatives who are female; and the lack of assertiveness among female artists have all been proposed as hypothetical causes. They are probably all correct, to some degree or another. Together, these and other mechanisms contribute to a “Matthew effect,” in which advantage begets advantage and starting over is not possible.

Theories for a gender wage gap

To propose that women and men make different kinds of art, and that this contributes to the gender gap in artistic valuation, strikes some as offensive. And in its extreme, or essentialized, version, the proposal is offensive. But when couched in history and sociological theories of gender, the proposal becomes a hypothesis to be tested, not just a claim to be rejected. It is a hypothesis that, if supported, would expand the mechanisms by which we understand inequality to reproduce across time and context, even as our judgments on the artistic talent of women progress. This hypothesis can be approached at first from a more general perspective, and then considered in the specific case of art. This is because a gender gap in wages exists not only in the art world, but also in the labor market at large.

Women’s involvement in the labor market began to surge in the 1970s, and since that time, economists and sociologists have sought to account for the differences in compensation between male and female workers. Generally speaking, these accounts have fallen into two camps: those that emphasize supply-side mechanisms, and those that emphasize demand-side mechanisms.

Supply-side mechanisms and the social construction of gender

Supply-side perspectives on the gender wage gap look to the characteristics of women and men as potential labor-force participants. Stated crudely, these perspectives argue that women earn less than men because they choose different training and occupations. It is still hotly debated whether women do so primarily for the sake of actual or expected motherhood responsibilities, but gender differences in college major and occupation selection have been widely documented. Indeed, supply-side explanations account for upwards of 50% of the gender wage gap in the U.S. alone.

Turning this supply-side perspective to the art world, the argument seems at first less robust. Women, as noted elsewhere in the Art Market 2019 report, major in the arts at higher proportions than men. An analogy can be drawn to job characteristics, however, and articulates as follows: part of why female artists earn less than men is that they produce art with different characteristics, be that in medium, size, style, or subject matter. This does not imply that any differences are a result of biology. Unsubstantiated and misdirected claims about the innate abilities and preferences of women and men, such as Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius’s claim that women do not think well in three dimensions, have little validity in light of the cultural forces that strongly pattern people’s lives according to their gender.

Sociologists have long insisted that cultural norms and expectations extend the concept of gender beyond biology and into the realm of social learning. Cultural gender norms that are learned in childhood and throughout contexts of adulthood shape everything from the color and cut of clothing and hair to preferences in hobbies and the age of romantic partners; the right to vote; the ability to travel; the amount of time spent with children and the elderly; and the probability of being president, a priest, or the victim of a violent crime. It is possible that both past and present gender norms also shape the characteristics of artistic production. If we expect that the artwork of artists may reflect their lived experiences, then we may expect that the shared experiences of men and women as groups could appear as differences in their art. In other words, the gender of artists may be one factor that shapes artistic choices in an otherwise heterogeneous object market.

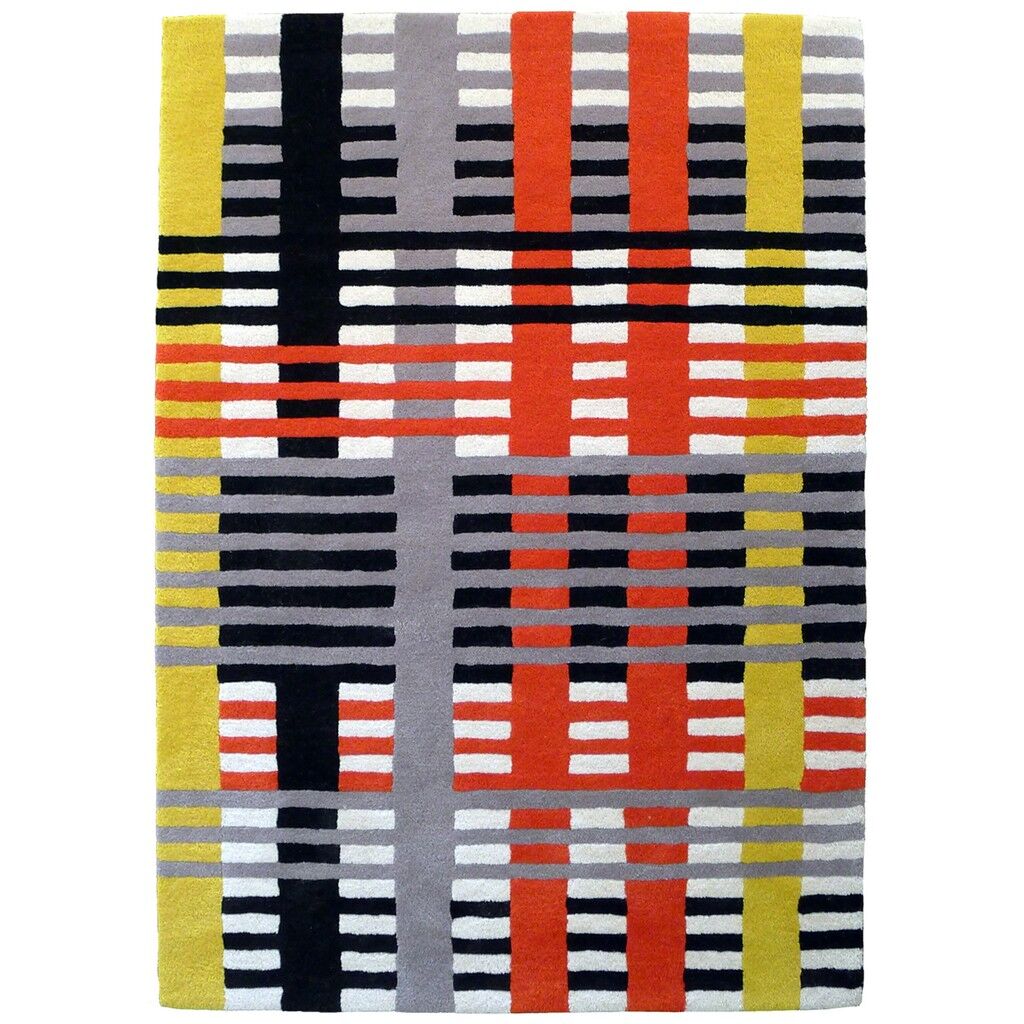

An example of artistic difference resulting from cultural gender norms is seen in the fact that there are more textile works by female than male artists in the

contemporary art market. Men are not unskilled or incapable of weaving, but one need not point to biology in any effort to explain why it is more common to see women producing textiles. In more explicitly sexist eras of art history, the textile arts were a medium that women were permitted and encouraged to adopt. One of Gropius’s conclusions regarding his belief that women worked best in two dimensions was that they should weave instead of study architecture or design. Not all women adhered to this injunction, but the copious amount of textiles produced by women in the Bauhaus era can largely be explained by it. The increasingly valued collections of Bauhaus textiles produced by artists such as Gunta Stölzl, Benita Koch-Otte, and Anni Albers, along with the traditions of female weavers across millennia and cultures, provide a lineage and language that burgeoning female artists may be more likely to pride themselves on as they envision their own work. This is an empirical question that could be asked to explain why textiles are more commonly produced by female artists, even today.

Demand-side mechanisms and discrimination

Despite their possible validity, supply-side explanations that emphasize differences in the characteristics of art by women and men are unlikely to match the more commonly offered demand-side mechanisms. Even in the general labor market, a gap in the wages earned by men and women remains after accounting industry, part-time work status, work experience, seniority, training, and other supply-side variables. It is at this point that scholars turn to demand-side mechanisms, including processes of discrimination and bias, to explain the remaining gender wage gap. Studies have repeatedly shown that employers are more likely to discriminate against women in job applications in some fields, and further indicate that women are judged differently from men by managers, coworkers, and consumers in regard to their competence, productivity, ability to innovate, and leadership style. This is especially true in contexts that are traditionally male-dominant.

In the art world, demand-side explanations for gender inequality point to the behavioral patterns of gatekeepers and tastemakers (for example, critics, curators, and dealers) and to a preference among collectors for works by male artists. In other words, demand-side explanations are the claims of discrimination and bias regularly discussed. Further research is needed to comprehend the full extent of their impact.

Yet while differences in supply- and demand-side mechanisms of inequality are useful to acknowledge, an important insight comes at their intersection. Considering again the case of textiles and the Bauhaus, the useful question may not be whether the men and women produced different types of work—because they did. Rather, we might ask why it took so long for the art world to value the characteristics of the Bauhaus women’s work, such as textiles. Surely it has something to do with the fact that women produced them. And even more importantly, are other qualities of art traditionally produced by women being similarly undervalued today? If so, their devaluation comprises a part of the puzzle behind gender inequality in the contemporary art market.

Why theories matter

Accounting for both supply- and demand-side explanations of inequality is necessary not only because good science will consider all reasonable hypotheses, but also because prescriptions of how best to reduce inequality will vary, depending on what perpetuates it. Demand-side explanations of inequality would insist that women be permitted into institutions and exhibitions without prejudice, and that their labor be valued equally when they complete the same work as men. Solutions in this realm may be like those devised by symphony orchestras, many of which now blind judges to the gender of the musician during auditions. In a study conducted in 2000, researchers found that the introduction of blind auditions increased the selection of female musicians by 30%. In some cases, the likelihood increased even further when candidates were instructed to remove their shoes, so as not to produce the give-away clicking of heels.

By contrast, supply-side explanations of inequality may require alternative solutions. If certain characteristics of art are more likely to appear in the work of women, then, as stated previously, the question is whether the characteristics themselves are undervalued. If so, a full solution would require not only that women’s art be valued equal to men’s for the same characteristics, but also that characteristics traditionally produced by women be valued equally to those traditionally produced by men or both sexes. The focus of efforts to reduce inequality would therefore include changing the underlying value framework to one that is less male-centric and does not inherently devalue artistic characteristics simply because they are or have traditionally been associated with women.

Online platforms—Artsy and The Art Genome Project

Answering questions related to gender inequality in the contemporary art world has been notoriously difficult. To test hypotheses of supply-side arguments, data is required not only on artists, but also on the qualities of the artwork they produce. Until recently, such data was not available. Online art platforms such as Artsy have changed this by unifying the fragmented pieces of the traditional art ecosystem into a single, centralized database.

Artsy maintains a global database of more than 1 million works by 130,000 artists. A large sample of artists and artworks in this database is described by The Art Genome Project, Artsy’s proprietary classification system and technological framework that connects artists, creators, artworks, and other creative objects, using more than 1,000 art-relevant features. These features describe such concepts as artistic disciplines, materials, physical attributes, styles and periods, object type, and geographic setting.

Is there gender inequality in primary online art markets?

To demonstrate an initial investigation of gender inequality with Artsy data, research was carried out on a sample of 108,654 artworks that have been produced since 1999 by a set of 11,675 individual artists associated with 2,069 galleries. These artworks have been coded by the taxonomy of The Art Genome Project, with an average of 24 artistic features applied to each, on a scale from 0 to 100, depending on how well the feature is represented in the work. To enter this sample, it was also required that the artwork have a listing price on Artsy.

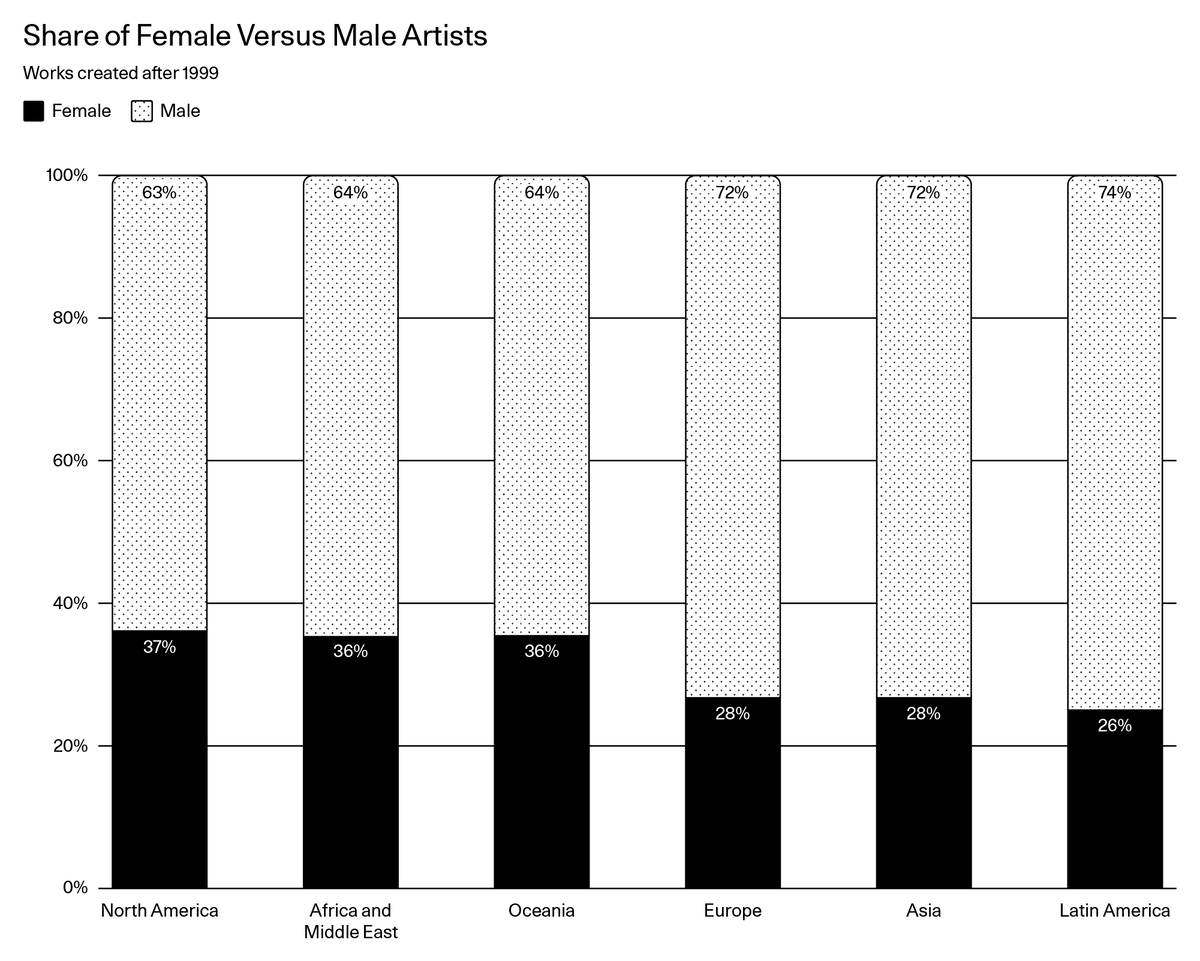

The median number of artworks by an artist in the sample was 16, with a small difference of 16 for women and 17 for men. Approximately 35% of the artists in this sample were female, and they produced approximately 35% of the artwork. This statistic varied somewhat across geographic regions, according to the location of associated galleries.

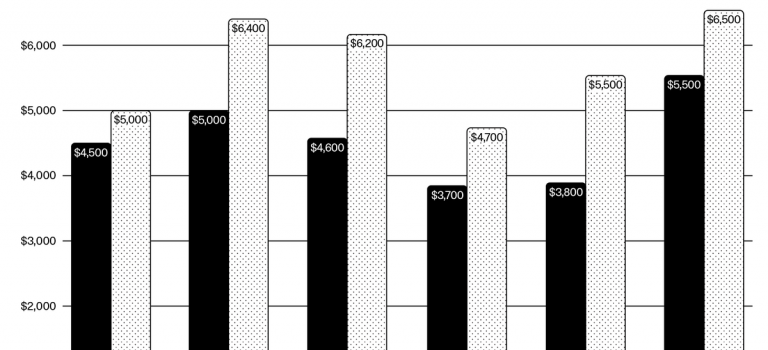

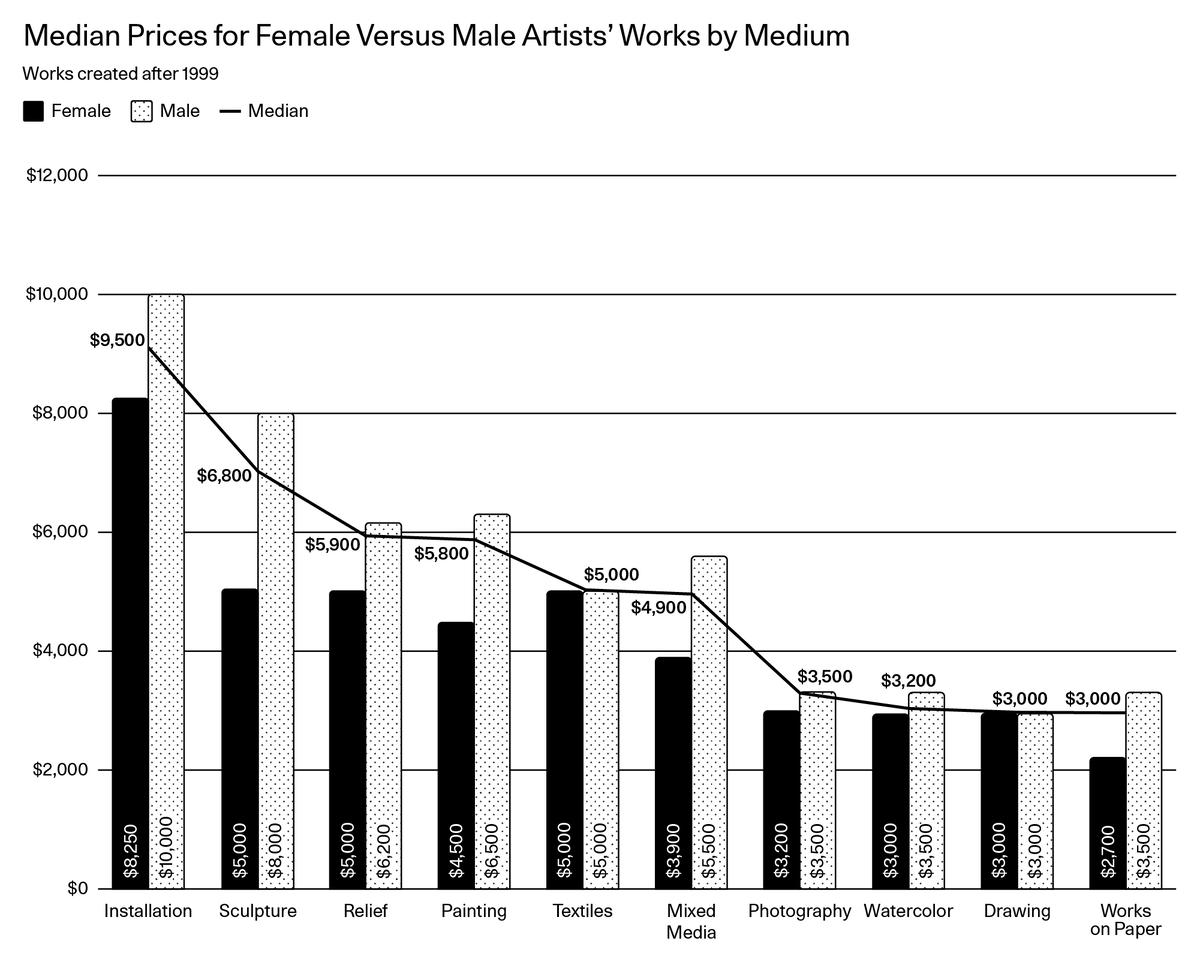

Using the gallery listing price for artworks as an outcome of valuation, there is evidence of a gap between men’s and women’s art. The median price for all works in this sample was $5,000, with an average of $14,670 due to significant skew in the listing prices of art, allowing some very expensive works to raise the average far above the median. (The maximum listing price for an artwork in this sample was $15 million.) For men, the median price was $5,500 (with an average of $17,160), while the median price for women was $4,000 (with an average of $10,070).

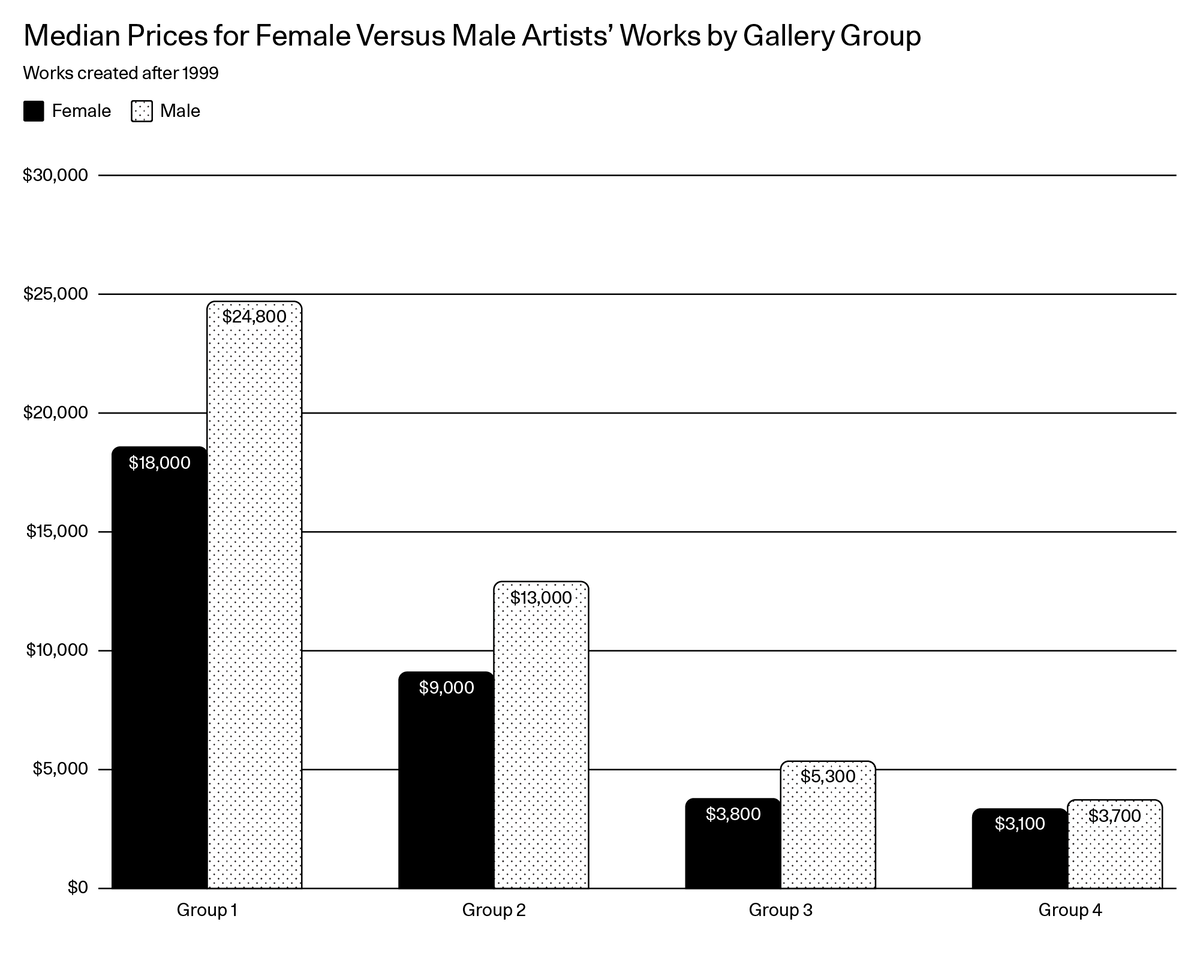

The gap between median prices for women’s and men’s artwork also varies by gallery group, which is a measure constructed to indicate a gallery’s engagement with the international art market through fair participation on a scale from 1 to 4. Group 1 aggregates “blue-chip” galleries that maintain multiple locations internationally and participate annually in global art fairs, while Group 2 encompasses established galleries that primarily operate in single countries and regularly exhibit at both international and national art fairs. Groups 3 and 4 both include regional and local galleries, distinguished by national fair participation for the former. For Group 1 galleries, women’s work had a median listing price 27% below men’s. This statistic was 30% for Group 2 galleries, 28% for Group 3 galleries, and 16% for Group 4 galleries.

However, care needs to be taken when interpreting these statistics, as they do not account for important characteristics, such as the size and medium of the works being offered. That such differences may influence price gaps is suggested by the fact that the median price gap varies across media.

Given this preliminary evidence of a gender gap in the primary art market, the aim, going forward, is to examine the mechanisms behind it. Specifically for this report, a brief foray into supply-side explanations is considered.

Recalling again that supply-side explanations for inequality focus on differences in the type of work produced by male and female artists, an initial question may be whether works by men and women in this online marketplace differ by size. They do not. For those artworks accompanied by a measure of size in the Artsy metadata, men’s work does tend to be larger, but this gap is not statistically meaningful.

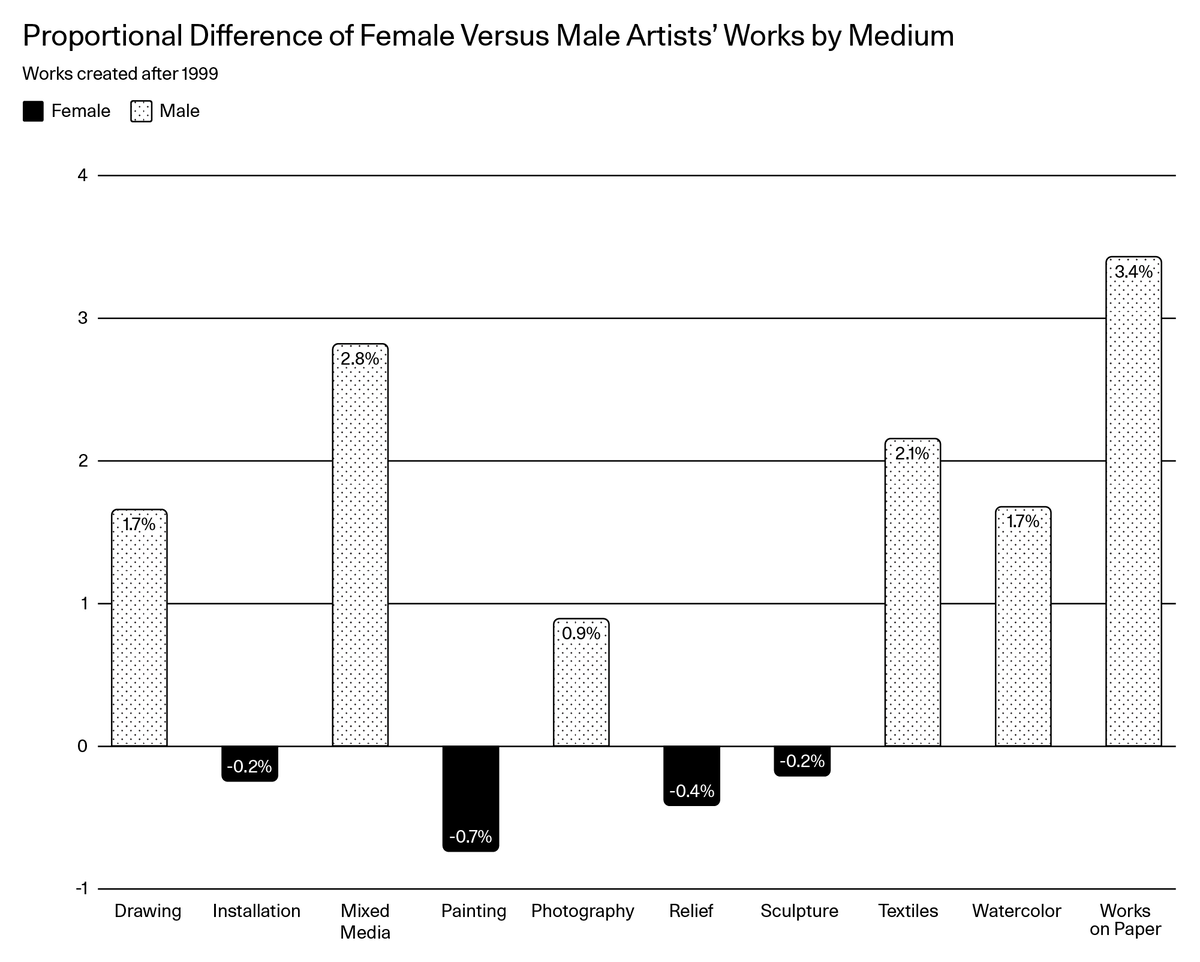

There is, however, some indication that men and women may differ in the media of art that they produce. The chart below depicts the proportion of artworks by men and women in 10 of the top media represented on the Artsy platform. Artworks are not limited to a single medium, and therefore may be represented in more than one category. The chart shows differences in the proportion of female and male work for each medium. For example, 11% of works by female artists on the platform are drawings versus 9% of the works by men, with a resulting difference of approximately 2%. Of the works by male artists, 54% are paintings versus 53% by women, with a resulting difference of approximately -1%.

The above chart indicates that, although they are small, some differences in the media used by male and female artists exist, with the notable observation that men remain the dominant producers of conventional media, such as painting and sculpture.

Drawing this inquiry further, basic log ratio analyses indicate that there are also differences in the 1,000-plus characteristics applied to the artworks by The Art Genome Project. That is, in some respects, women and men produce different characteristics of art according to this taxonomy. Although the large majority of features show no substantive difference by gender, there are those that do. Analyses in ongoing research further suggest that, provided with these features of The Art Genome Project, a machine learning algorithm can classify art by the gender of the artist with a relatively high degree of precision. How this finding maps onto the claim that women and men make art with different characteristics is a central focus of the research.

If the preliminary finding that men and women, in some respects, produce art with different characteristics is upheld by further scientific scrutiny, then the next step is to investigate whether the characteristics more commonly appearing in women’s work are also associated with lower prices or other outcomes of artistic value. If so, then the undervaluation of “female” characteristics may contribute to our broader understanding of gender inequality in the art world. Evidence that this hypothesis could be upheld is provided by a small but negative correlation found between the odds of an Art Genome Project feature appearing in women’s, as opposed to men’s, artwork and the listing price of the artworks displaying that feature.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once quipped that “sociology and art do not make good bedfellows.” His reasoning was grounded in the tension between the art world’s desire to focus on individual creative genius, and sociology’s insistent aim to explain phenomena in terms of social forces. Who and what defines art and quality, which institutions matter and how they are accessed, who knows whom, whether advantage is accumulated from a prejudiced past, and where conscious and subconscious biases of culture interrupt economic valuation—these are the questions that sociologists ask to explain greatness. It is not a denial of quality, talent, innovation, or genius, but a way to contextualize them.

As shown here in a brief analysis, efforts to analyze this context in the domain of the contemporary art world can be aided by online art platforms. Data from these platforms help answer not only questions about gender, but also race and ethnicity, age, career stage, and socioeconomic status. And not only about inequality, but also networks and curation, the shifting influence of roles and institutions, the position of art in social life, the tastes and demographics of collectors, and the emerging sway of algorithmic recommendation systems and social media. In other words, the marriage of these platforms with scholarly research will teach us more than ever before about the roles, patterns, and processes that together (re)produce the art world as we know it.