Source: NY Times.

Collecting fine art is as much about beauty and desirability as it about the investment value. Given how strong the art market has been over the past few years, many collectors may not be prepared if the economy slows and the appetite for art cools. Paul Sullivan of The New York Times examines art as a valuable but illiquid asset.

The value of a Picasso or a Ferrari typically rises in a strong economy, as do shares in a consumer staple like Procter & Gamble.

But when the economy sours, those shares may be easier than the other possessions to shed. As wealthy collectors pull back on extravagances, investors could get stuck holding an asset they might have to unload at a loss.

In 2012, when the market was roaring for passion assets — those in which you put money where your heart is — I wrote a series of columns on why people invested in things like vineyards, racehorses and sports teams.

This time, I will look at five nontraditional asset classes that are popular with wealthy investors and with an eye on what to expect in a market downturn. Art is the first of five valuable but illiquid assets I plan to examine in the coming weeks. The others are cars, collectibles like wine and jewelry, private equity and real estate.

Collecting fine art is as much about beauty and desirability as it about the investment value. Given how strong the art market has been over the past few years, many collectors may not be prepared if the economy slows and the appetite for art cools.

Roy Sebag, a hedge fund analyst turned entrepreneur, has a collection that includes a drawing by Pablo Picasso and works by 17th-century Dutch masters. He said he took an objective view of his collection’s value: looking at both the art’s intrinsic value — how an artist’s work has appreciated — and its social currency.

“It’s subjective,” but it still allows for analysis on historical pricing, said Mr. Sebag, founder of Goldmoney, a site for buying and selling precious metals, and co-founder of Mené, a jewelry line. “It isn’t a coincidence that Picasso is viewed by every high-net-worth individual as an asset they want to own.” There are supposedly 5,000 works by Picasso, he said, a stock large enough to build a network of interested parties.

By his analysis, avoiding emerging artists and buying works of a well-known artist like Picasso, despite having to pay millions of dollars to do so, is like buying a hedge against recession. “We know trends change quickly,” he said.

Such beliefs could be tested in the next few years.

In 2018, works by the 100 top-selling artists, as measured by the market research firm Artprice, rose 4.3 percent in value, but the art market as a whole lost 1.9 percent. The company explained that buyers were becoming more demanding.

“While happy to pay big money for rare and high-quality works with irreproachable provenance, they often ‘pass’ on other works,” its report said.

In 2008, the art market was not immune to huge swings in value. Sales of postwar and contemporary art fell by more than two-thirds from 2008 to 2009, according to data collected by Athena Art Finance, which lends against art portfolios. It took until 2012 for sales to surpass pre-recession levels.

To guard against seeing the value of an art collection plummet, dealers advise prudence and, not surprisingly, connoisseurship.

If there is a lesson to be drawn from the recession, it is that buyers become more discerning in both the artists they favor and the price they will pay, said B. J. Topol, co-president of Topol Childs Art Advisory, which works on behalf of wealthy clients.

“There’s a reshuffling in a recession,” she said. “The trendy artist of the time, people aren’t looking at him. People want to make sure they’re buying a known commodity and not taking risk.”

Ms. Topol said she saw signs of a slowdown in the art market at the Art Basel international art fair in Miami Beach in December. Art wasn’t being snapped up in the first few minutes. Instead, buyers had a chance to digest what they were seeing and negotiate on price.

Regardless of the climate, she advises not to buy on trends, yet she stops short of the adage to buy what you love. That could be financially disastrous.

“If you combine your passion with an informed decision,” she said, “you’ll have something you love every day and maybe it goes up one day.”

Other collectors amass idiosyncratic collections whose value is greater together than apart. Peeling off several pieces in a downturn could depress the value of the collection as a whole, said Jean Pigozzi, a venture capitalist and art collector.

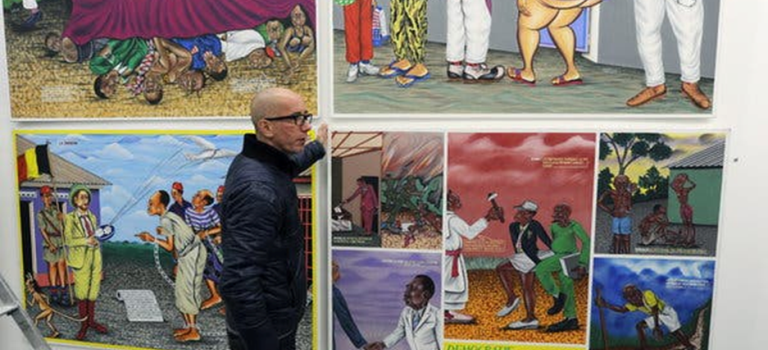

“I’m not at all like all the other hedge fund collectors,” said Mr. Pigozzi, who has amassed a significant collection of contemporary African art. “I’ve never collected thinking what I collect would be a good investment.”

He said most of his pieces were not worth more than $100,000. Compare that with a work by Jean-Michel Basquiat, among the best-selling contemporary artists today. Mr. Pigozzi paid $1,000 for an artwork by Basquiat in 1982 and sold it last year for $3.2 million.

What he has is a unique collection that is often included in museum shows and sought after by auction houses. In its totality, it offers a window into sub-Saharan art of the past 30 years.

But Mr. Pigozzi knows selling it would be difficult without breaking it apart. Instead, he hopes to create a museum for it.

Approaching art as a pure investment can be difficult, because values of an artist’s work can change substantially in ways not associated with typical capital markets investing.

The value of works by Wifredo Lam, for instance, has doubled or even tripled in the last decade because of a reappraisal of his place in art history, said Isabelle Bscher, the third-generation owner of Galerie Gmurzynska, which has represented artists including Yves Klein, Joan Miró and Picasso.

Lam, who died in 1982, was Cuban by birth and grouped with other Latin American artists at auctions, which drew a specific collector. But he was later seen as a modern artist, because he was a friend of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and other midcentury artists. As his artworks moved to more popular auctions, their value has doubled or tripled in a decade, Ms. Bscher said.

A similar shift happened with Picasso about 15 years ago, she said. Collectors did not want to buy his work created after 1965, when the artist was in his 80s and seen as past his prime. At the time, the artworks were inexpensive, but they have since risen in value.

Her advice: “If you buy the period of an artist that is not in fashion, you can make a great investment.”

There are of course plenty of collectors with enough wealth to not really care about the short-term hit in value that the work on their walls may take. Hilary Geary Ross, an art collector and the wife of Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, said she had always loved the work of René Magritte, the Belgian surrealist, and began buying his work when she and Mr. Ross married in 2004.

She has 36 pieces by Magritte, worth in excess of $100 million. They include famous works like “La Clairvoyance.” The billionaire couple have rarely sold any of their works, but Mrs. Ross said they did take advantage of the 2008 downturn to buy paintings.

“People come to us with them, because they know we like them,” she said.

In distressed markets, social concerns may keep some people from working with auction houses. They can try private sales — as happened with the Ross’s acquisitions in 2008 — to sell something quietly.

But Ms. Topol said that even then, discerning collectors were going to drive a hard bargain. If that happens, she said, dealers and auction houses can step in to help. But her advice echoes that of others: Don’t sell art in a downturn unless other sources of liquidity have dried up.

Mr. Sebag said that the art he owned had increased in value far more than other investments he had made, but that he would sell it only if he ceased to enjoy it.

“I think art is something you purchase without an exit strategy,” Mr. Sebag said. “My idea of liquidity is in other investments.”

Having those other buckets to draw from is important — otherwise, you could be forced to sell a prized work for less than you would want to when the economy sours.